The following was written for The Real Deal, and published in the special New Jersey section on June 6, 2016. The piece was highlighted on the cover. You can read the original here.

It’s no secret that Brooklyn has experienced a transformative renaissance in the past decade. And while many cities in and around the New York metro area seek to have their own similar successes, it has been said that select parts of New Jersey are poised to truly become the “spiritual twin” of the borough.

In fact, The Real Deal explored the topic with Jersey City last June — highlighting the Brooklyn-esque artist community the area is now attracting. Meanwhile, Hoboken and Newark have also sought the type of redevelopment that emulates the upward trajectory of the outer-borough success story.

But the prevailing question is: Can Brooklyn’s unique recipe for success be replicated across the Hudson River? Thanks to a complex cocktail of factors, the resulting answer is simple: not likely, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“A large part of growth in Brooklyn has centered around the repurposing of older warehouse spaces and hip residential neighborhoods, all in the notion of ‘live, work, play,’” said Steven Bleiweiss, a senior vice president at the Rutherford-based commercial brokerage firm Cresa NJ. “We don’t see a lot of that concept within these three cities.”

Thanks to readily available transit access, rents that are still approachable for young upstarts and neighborhoods that have their own distinct looks, the theory of becoming the next Brooklyn seems easy enough to execute on paper. But in practice, real estate players and other industry leaders are grappling with crumbling infrastructure, soaring construction costs and strong competition.

In the case of Newark and Jersey City, a distinct lack of residential units has dampened the ability to sustain retail opportunities outside of the traditional nine to five working hours, Bleiweiss noted. At the same time, “Hoboken is an already established community, but limited,” his colleague Thomas Giannone, a managing principal at Cresa NJ, said.

Hoboken residents relax with views of Manhattan.

And there are after-effects to experiencing the type of growth Brooklyn has seen. From clashes between old and new residents — as the borough’s neighborhoods work to identify themselves in the new norm of gentrification — to ever-rising rents that cater to a ravenous luxury market, Brooklyn is transforming into something that was almost unthinkable 20 years ago.

While Brooklyn’s growth has outpaced the capacity of its infrastructure, New Jersey’s biggest cities have seen their assets be both undervalued and underutilized, according to the commercial brokers.

Of course, investors, developers and policymakers rooted in New Jersey see the necessity of finding creative solutions to overcome the urban planning challenges in each city, but they also realize that being the next Brooklyn just isn’t in the cards for them. And none seem too upset about it.

“It’s my hope and belief that Jersey City will not become the ‘next’ anything,” Jennifer Morrill, Jersey City’s press secretary, told TRD. “At the end of the day, it’s Jersey City’s own unique and diverse culture that makes it so special. We plan on keeping it that way.”

With the real thing just a short train ride away, there’s also the the question of why buyers would want a simulation of Brooklyn across the Hudson.

Hoboken, Newark and Jersey City may seek to become grander versions of their respective pasts, but those on the ground there say don’t call them the next Brooklyn.

Hoboken

In the wake of Superstorm Sandy, Hoboken is looking for the best way to adapt to the New York metro area’s ever-changing real estate environment, as well as fortifying itself against future storm damage.

Facing ample development pressures, including a high-profile redevelopment proposal over New Jersey Transit Corporation’s 52-acre rail yard site, Hoboken’s officials are struggling with the notion of allowing unfettered, urban growth. The city council approved a 2.2-million-square-foot mixed-use project in December 2014.

Hoboken Mayor Dawn Zimmer, who assumed office in 2009 as the city’s first female mayor, stressed her commitment to following proper urban planning practice.

Hoboken Mayor Dawn Zimmer

“We’ve been very focused on investing in infrastructure,” she toldTRD, adding that she believes maintaining fairness is the key to Hoboken’s successful redevelopment. Zimmer added that the city’s efforts to nurture growth have been rooted in community participation and that developers have responded positively to the city’s dedication, while several large companies have recently signed office leases there.

In February 2014, Thompson Reuters committed to expanding its footprint four times over on the city’s waterfront, according to the Star-Ledger. The expansion included the relocation of 450 workers to the area after receiving almost $26 million in tax breaks from the state.

And this March, Jet.com opted to double its presence to 80,000 square feet at the 1.5-million-square-foot Waterfront Corporate Center complex owned by the Parsippany-based development firm SJP Properties, a major player in New Jersey’s real estate scene.

“Hoboken is a preferred destination for startups and companies that are experiencing or anticipating substantial growth,” said Peter Bronsnick, a senior vice president at SJP. “Waterfront Corporate Center is one of the very few state-of-the-art, Class A office buildings on the waterfront, just steps from transportation.”

Meanwhile, Zimmer said her office is working to improve resiliency to storms after 80 percent of the city became flooded in 2012 during Sandy. Thanks to low interest loans and cooperation from state and federal sources, Hoboken has been able to spur more commercial development and create more public transportation options, she added.

“We must put much more focus on transportation connections to New York City,” the mayor said when asked about the city’s relationship with the five boroughs.

But rather than aiming to be the next Brooklyn, Hoboken is instead opting to pursue its own destiny, she noted.

“Hoboken is Hoboken,” Zimmer said. “We’re very cool. We’re focused on commercial development more so than residential, and the creation of more jobs.”

Newark

Farther west in New Jersey’s largest city, developers and policymakers are taking a different approach and are focusing on efforts to reinvigorate the many underutilized infrastructural assets, such as transit access and surplus student capacity in the schools, within the municipality.

But looking to pump new life into Newark’s deteriorating industrial sites, as well as working to combat stagnant economics, a drinking water crisis and a higher-than-average crime rate, has been a challenge, according to local developers who spoke with TRD.

Ron Beit of RBH

Still, Newark is just 20 minutes from Manhattan by train and such proximity presents ample investment opportunities, several local real estate players noted. Now, a growing number of developers are being lured by low real estate prices and empowered by the continually rising rents in New York City.

The insurance giant Prudential Financial, which was originally founded in Newark, expressed its commitment to the city by announcing a brand-new $444 million office tower to call home, while the area around the Prudential Center is being targeted for ample redevelopment of its own.

With vacancies climbing as developers work to turn Newark around, the area is still actively seeking investment. As such, Newark isn’t going to be the next Brooklyn anytime soon, but some developers say they have grander aspirations for the beleaguered city.

“Honestly, I think Newark can become better than Brooklyn,” said Ron Beit, a founding partner and the CEO of the Newark-based development firm RBH Group. “Brooklyn’s growth is a series of pockets, a bit disjointed, while Newark has the historic street grid and infrastructure to be cohesive.”

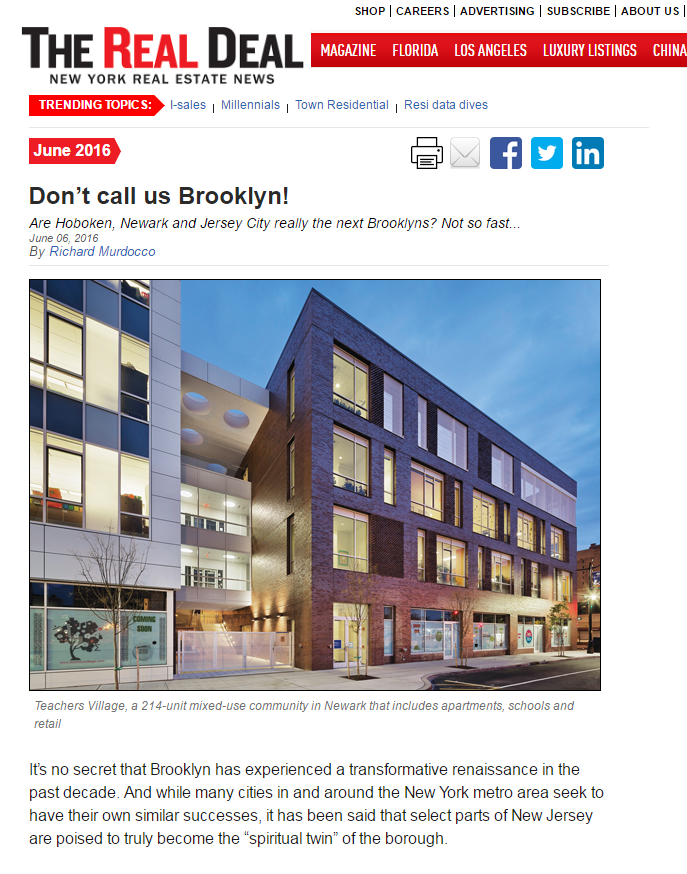

RBH owns 79 parcels in the heart of the city and is responsible for the creation of the 214-unit Teachers Village, a mixed-use community that includes schools, rentals geared toward teaching professionals and retail space. The firm’s latest endeavor is the $410 million Four Corners Millennium Project on the corner of Broad and Market streets, which is expected to convert idle commercial and industrial usage into more than 800 apartments, while adding an additional 135,000 square feet of retail.

“First and foremost, if there was no public support from the city and state, our projects wouldn’t be,” said Beit, citing the changes of financing that the public sector helped enact in the form of ample tax breaks and governmental subsidies from the state’s economic development and housing agencies.

He also pointed to the turnaround he has seen in the area over the past few years. “I could never believe Newark was so underdeveloped,” Beit said.

Jersey City

In stark contrast to Newark, Jersey City has continued to thrive since the high-rise towers at the Exchange Place financial district rose as part of the revitalization of the city’s waterfront in the early 1980s.

A majority of new, large-scale development has occurred in Jersey City’s downtown since then, but in recent years that growth has pushed to other areas such as Journal Square, in the western portion of the city, and the historic downtown area.

Hamilton Square, a condominium built by Silverman in Jersey City, the state’s fastest-growing municipality.

As the fastest-growing municipality in the Garden State, Jersey City is expected to soon house a 79-story tower, which at 900 feet tall would become the tallest in the state. The project, 99 Hudson Street, successfully broke ground in January 2016 and is scheduled for completion in 2018. China Overseas America Incorporated — which is spearheading the project on behalf of its parent company China State Construction Engineering Corporation — announced that the $500 million mixed-use tower would include 781 condos in addition to retail space.

“We are committed to developing this iconic project on Jersey City’s waterfront,” said Cindy Xiu, president of China Overseas America Incorporated, in a statement issued at the time of the project’s groundbreaking. “This is indicative of the continuing growth of Jersey City,” she continued before going on to compliment the city for its “vision.”

As of February 2016, a total of 27,311 residential units were either proposed, approved or under construction in Jersey City’s downtown area, according to the city’s planning division. Journal Square alone is expected to see an additional 10,338 residential units at some stage of the development pipeline, the numbers show.

Paul Silverman, a principal at the Jersey City-based development firm Silverman, said he believes the city and its local agencies and utilities have set the stage for success.

“They’ve helped us with new wastewater pipes and storm drains to support our projects,” the developer, who has been actively working in the area for 35 years, told TRD. He said the utility company helped install new plastic gas lines after Hurricane Sandy.

Yet, public transportation in the area has lagged behind its development, Silverman noted. After a group of developers pushed the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey for improvements, the interstate joint venture announced plans in recent years to roll out new technology that will allow for more trains with more frequency and expand its stations to allow for 10-car stops.

“Everyone is aware of the increased demand development places on the PATH system,” Silverman said.

Nevertheless, unlike Brooklyn, Jersey City is “big enough for us to build our projects yet small enough to see people you recognize in the streets,” he added. “My brother and I are often asked to build in New York City, but if we did, we’d be one of hundreds of developers. Here, we build, and we’re one of the few. It’s great to see projects bring life to formerly empty sites.”