The following was written for the Long Island Press. You can read the original here.

Long Island is experiencing a welcome renewed boom of housing construction. But are we pricing out the region’s young families by building exclusively for the elderly? Shouldn’t we be catering our downtown development proposals to the supposed wants of millennials? Or are we missing the boat completely by failing to address the true drivers of housing costs in the region?

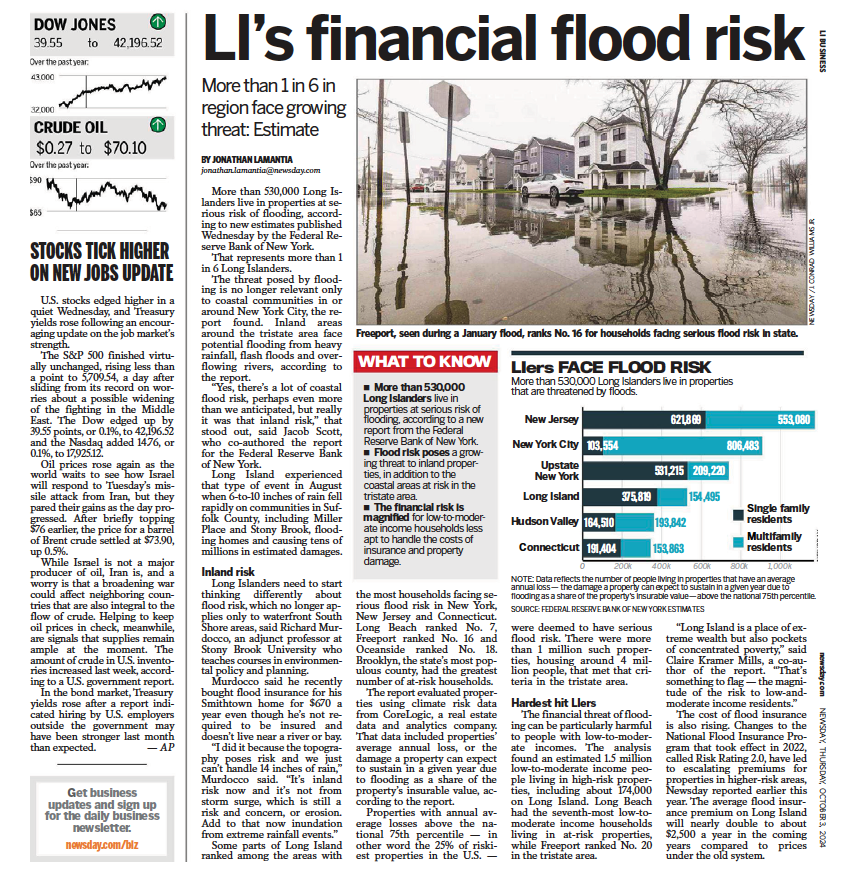

While Nassau and Suffolk counties are often called “The Land of No” when developers are asking the question, the figures, showcasing both historic and recent building permits, don’t lie. In recent years, LI has seen an uptick in housing starts, especially when compared to the years of the Great Recession. Throughout the 1980s, Suffolk saw an increase of more than 5,000 multifamily units. The average increase remained fairly static at 5000-plus from 1990 to 2000, but the last decade or so is a different story. From 2000 to 2010, Suffolk saw more than 15,000 units of multifamily housing built – triple the rate being built in the last 20 to 30 years.

The number of senior housing units is ballooning as well. In 1980, there were 5,000-plus units of senior housing in Suffolk. By 2014, that total number grew to more than 25,000 – and more units are being added. Clearly, the supposed “Land of No” has seen year-over-year increases in housing. But prices remain on the verge of unaffordable, so it seems that building more units is doing little to alleviate the Island’s housing cost woes.

Demographically, LI is aging. According to the U.S. Census, the Island had more than 324,000 residents aged 65 and older in 1990. By 2013, that total swelled to over 441,000, with more elderly expected to proliferate as the Baby Boomers leave their younger days behind. Compare the growth of this demographic segment to the ever-critical decline of millennials that LI policymakers always seem to grimly tout.

In 1990, the Island had 626,000 residents aged 20 to 34, but by 2013, the region saw the total drop to 500,000. Yet, this supposed Brain Drain represents an actual gain since the region had 478,000 people in this demographic group in 2010. Luckily for Long Island, the 5-19 age range has 582,000 residents in the pipeline, so all is not lost.

Why the lesson in the number of housing starts and the cyclical nature of demographics on LI?

It is important to understand these trends because making policy, especially housing strategies, based on age demographics—and age demographics alone— isn’t sound planning. In fact, it ignores the true causes of concern especially regarding housing.

Ever-increasing costs, a symptom of the Island’s lack of economic opportunity due to the proliferation of low-wage service sector growth, is the serious issue we must address. In the past two decades, construction has inched along, yet companies are still fleeing our region. While local policymakers and developers play Chicken Little by claiming the sky is falling due to the Brain Drain, what they should dread is not the flight of the young or the lack of housing for the old – it’s reigning in the cost of living on Long Island.

Some argue that increasing the region’s housing supply is the answer, but this blind adherence to supply and demand economics ignores the fundamental reality that Long Island is environmentally fragile thanks to its sole-source aquifer, it is surrounded by water and its vacant open space is limited.

There is no simple answer, but a good place to start would be the creation of high-paying, quality jobs that take advantage of LI’s educated workforce. The Island needs a vibrant, diversified economy with multiple sectors that foster business-cycle resiliency while offering opportunities for all types of workers. Policymakers must take a serious look at Long Island’s economic and racial segregation – and conduct an honest analysis of what, exactly, is driving up housing costs.

Is it “exclusionary zoning” as urbanists often claim? Or are Long Island’s balkanized school districts, fire districts and countless other political and quasi-political overlapping fiefdoms to blame?

Until these hard questions can be answered honestly, our policies will continue to be misguided by anecdotal evidence, stakeholder whims and insiders’ political savvy – while our corporations flee and housing affordability slips ever further away from those who would pay to stay.