The following was written for Boating Times Long Island’s July issue.

You can read the original version here. You can find a list of locations where Boating Times Long Island is distributed here.

Carol. Donna. Gloria. Bob. Irene. Sandy. The names are part of our history. Since the 1930s, Long Island’s storm vulnerability has been known, yet little was done until 2011 when Irene, a relatively small hurricane, hit the region. When Sandy struck the following year, a sense of immediacy for storm preparedness resonated with policymakers.

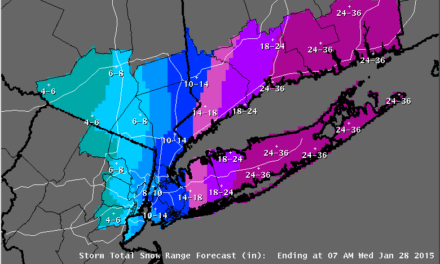

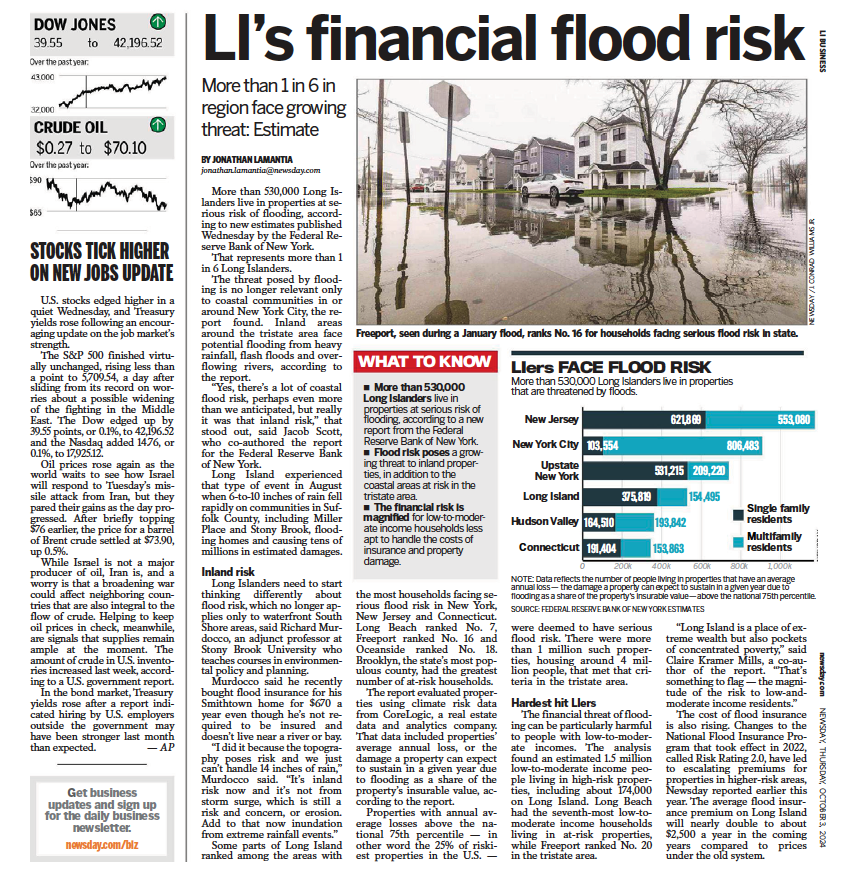

Despite the politically attractive zeal for storm hardening, our region is still vulnerable to future storm threats and may be unable to adapt itself to the new normal of extreme weather events in the 21st century.

On October 28, 2012, an overcast and nervous calm hung over the Robert Moses Causeway in West Islip as the Great South Bay — still as glass — flowed beneath the crossing. Twenty-four hours later, Hurricane Sandy, soon to be dubbed a “Superstorm” by local media, rumbled and churned up the eastern coast, taking a sharp turn and hitting our tristate region dead on. By October 30, the calm had returned, but to local residents, Sandy’s presence was felt for weeks, months, and years after the storm dissipated.

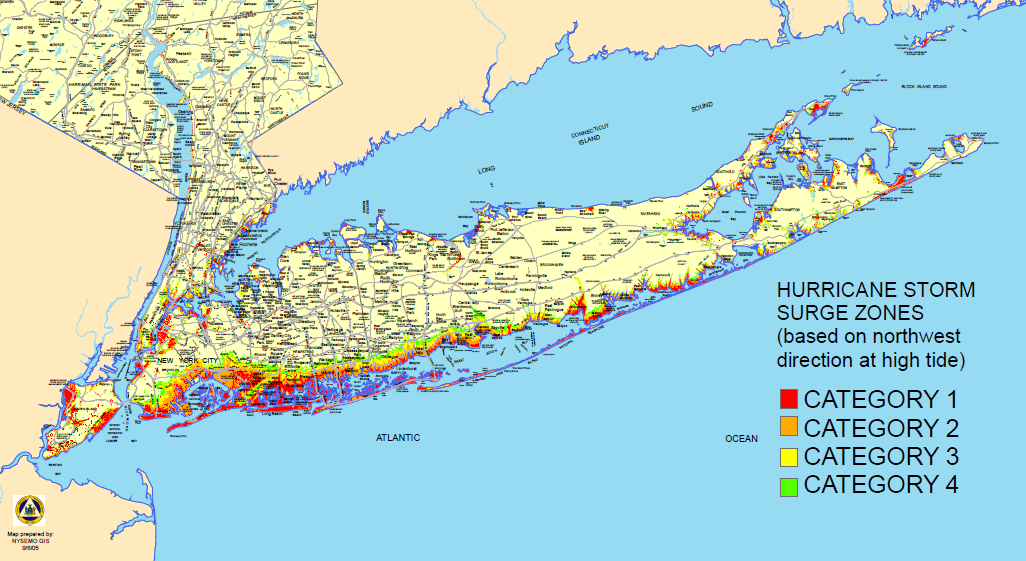

As horrible as Sandy was for Long Islanders and the surrounding areas, the storm was classified as barely a Category 1 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. When compared to the 1938 “Long Island Express,” a forceful Category 3 storm that is considered by most as the benchmark for our regional hurricane threat, Sandy was weak. Yet this weak storm displayed just how vulnerable our region is to a storm surge.

In Sandy’s wake, flood-prone areas of Nassau and Suffolk experienced record damage that local, state, and federal governments are still struggling to quantify and repair. Many people asked why Sandy hit the region as hard as it did.

The answer lies with the suburbanization of Long Island’s coast. It started with the sporadic placement of beach bungalows after the Great Depression and exploded with the rapid development of large subdivisions where wetlands once stood. As Dr. Lee Koppelman, Long Island’s veteran planner and executive director of Stony Brook University’s Center for Regional Policy Studies, told Newsday’s Nicholas Spangler shortly after Sandy hit, “Builders were able to get land as relative gifts. We lost more than two-thirds of the natural wetlands that existed at the beginning of the 20th century.”

As Spangler wrote at the time: “Thousands of houses were built with ‘no plan and no control,’ he [Koppelman] said. Some were summer bungalows, winterized and turned into year-round homes. Most were built on slabs instead of pilings, sitting low on ground that itself was rarely more than a couple of feet above sea level.”

Development crept eastward from Oceanside to Mastic Beach, extending to within mere feet of the waterfront. Development patterns showed little respect towards Long Island’s known floodplain and areas with a high risk of erosion. The impacts of coastal development sapped the Great South Bay of eelgrass, essential for keeping the coastal sands from shifting. Storm after storm, ranging in size from hurricanes to nor’easters, waterfront residents first saw the coast erode and their yards flood thereafter. Eventually, every storm event was a near-guarantee to result in property damage.

Cheap, federally backed flood insurance kept coastal areas viable for continuing development; until Sandy, flooding was more of a hassle than anything else. When Sandy hit, the storm gave Long Islanders a new, darker perspective on their previously romanticized coast.

Long Island’s vulnerability cannot be taken lightly. Thanks to hard infrastructure improvements like fortified bulkheads, strategic placement of new dunes, and property buyouts fueled by federally sourced relief funding, the region is better off now than in October, 2012. However, this region is just biding time until the “Next Big One.” We cannot afford to rebuild only to the status quo; the lessons learned after Irene and Sandy should dictate where future growth will (and will not) occur.

Planners generally consider Long Island’s floodplain as the area that stretches south of Sunrise Highway (NY 27) from the Queens line to the village of Rockville Centre, and south of Merrick Road/Montauk Highway (NY 27A) to the eastern tip of the Island. The Island’s South Shore is the home to some of the densest population centers on Long Island, and it is imperative that we protect these communities from future storms through smart infrastructure upgrades.

Priority should be given to the elevation of housing units, continued placement of natural vegetative buffers, and the restoration of both natural wetlands and eelgrass in the Great South Bay. On Fire Island — the barrier beach whose geological purpose is to protect the region’s vulnerable South Shore from the pounding surf — residential development was never appropriate. Sandy’s impacts show just how dangerous it is to continually rebuild on the ever-shifting sands. We need to balance our hard infrastructure upgrades with soft, green solutions to maximize the effectiveness of both. Every resident and decision-maker knows more storms are coming.

Will we be prepared?