The following was exclusively published by The Foggiest Idea on November 1st, 2022.

This piece was honored with a first place prize for weather reporting by the Press Club of Long Island in their 2023 PCLI Media Awards competition. Interested in supporting The Foggiest Idea’s award-winning reporting and analysis? Click here.

Ten years after Sandy, the silver lining from that super storm is stronger forecasting protocols as bad weather systems become more unorthodox.

BY RICHARD MURDOCCO

When Hurricane Sandy began its sweep up the Eastern Seaboard in late October of 2012, Craig Allen, chief meteorologist on WCBS News Radio 880, grew increasingly concerned by the data coming in.

According to the Euro, one of many predictive models that forecasters cobble together to hash out a cohesive, workable prediction, Sandy would take a sharp leftward turn west into the Jersey Shore roughly 60 miles south of Long Island. Under normal circumstances, storms like Sandy typically ride the coastline northward and pull to the right – either brushing by Cape Cod or wandering harmlessly out to sea.

Recently, on a brilliant autumn morning nearly a decade later, Allen recalled the growing fear he and his weather colleagues felt as the models further converged – each one showing that sharp westward hook.

“All of us were talking a week in advance after models suggested the turn,” he said. “Every day, Sandy was more firmly locked into this path. It became scary.”

At the time, the storm was still churning with Category 2 strength on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, which classifies hurricane systems based on their sustained wind speeds. According to the National Hurricane Center (NHC), Sandy was an extraordinarily large storm in terms of its sprawling footprint, and the storm’s sustained winds, which were roughly 97 mph at the time.

“While we knew it was going to weaken, we didn’t know by how much,” he recounted.

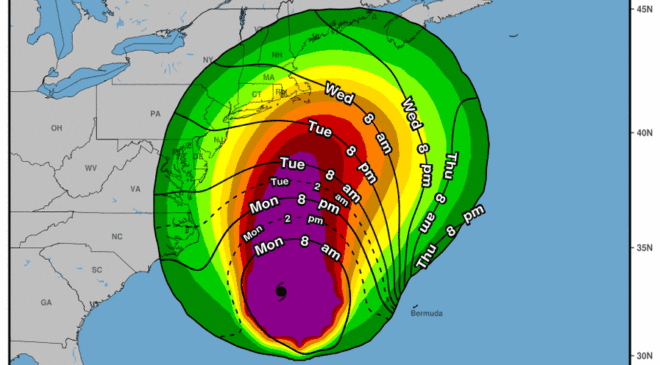

As Sandy’s landfall on the eastern seaboard neared, forecasters grew increasingly concerned by the storm’s pronounced “left-hook.” (Photo Credit: National Hurricane Center)

To make matters worse, the NHC was hesitant to issue the myriad of hurricane or tropical storm warnings for the New York/New Jersey area despite what it had already done further down the East Coast.

This issue was due to the complexity of Sandy’s composition, which presented unprecedented challenges for storm forecast and warnings. Though the sprawling storm was still predicted to be deadly, it was technically expected to be a post-tropical system at the projected time of landfall and not a hurricane in the traditional sense. As such, any existing hurricane or tropical storm watches and warnings would expire, regardless of the storm’s strength.

Unfortunately, Sandy broke the NHC’s advisory system, and there wasn’t enough time to create a new one.

Three days prior to the storm slamming the Jersey Shore, the National Weather Service opted to issue non-tropical warnings and watches about the coming winds and flooding risks through their local Weather Forecast Offices. These high-wind and coastal flood watches and warnings stressed the risks the cyclone posed, but the lack of Sandy’s hurricane classification had lasting unforeseen repercussions for the forecasting agencies themselves, for homeowners looking to rebuild, and for the insurance companies long after the floodwaters receded.

But until then, the Northeast did not have a recent example of the fury these cyclones bring.

Allen noted that Tropical Storm Irene, which hit our area in 2011, was forecasted with much of the immediacy used for Sandy a year later. In the end, Irene did not do as much visceral damage as was expected.

“It did not hit ‘right,’ ” Allen told TFI. “People had this idea of what a tropical storm would be like based on Irene.”

This bias left few in the region with little else to compare Sandy’s threat to, as Allen explained.

“The last bad storm was the 1938 hurricane,” he said, referring to the infamous Long Island Express, a forceful storm that carved across the East End with Category 3 force. “There was nothing recent to compare Sandy to. So naturally, people compared it to Irene.”

Sandy forcefully struck at high tide during a full moon on Oct. 29, 2012, making the pronounced leftward hook that Allen had seen the models predict a week or so earlier.

Hitting at high tide during a full moon, Sandy left many areas across the region inundated with storm surge. (Photo Credit: Rob Simpson, US Coast Guard)

Now 10 years later, Sandy’s aftermath has led to substantive changes in storm nomenclature and classification at both the NHC and NWS.

“There have been major changes in directive on how to handle tropical systems when they become post-tropical,” Allen explained. “Unfortunately, it took all this damage and death, but at least now there is a better understanding.”

To their credit, both federal weather agencies quickly moved to revise their longstanding forecast protocols and procedures.

Nine months after Sandy, it became policy for all relevant watches and warnings to be issued or remain in effect after a tropical cyclone becomes post-tropical. Since 2017, the NWS has been issuing storm surge watches and warnings in areas that face significant risks from a cyclone, regardless of the weather system’s officially designated tropical status.

Even potential tropical systems now have watches/warnings issued by agencies as needed. According to the NWS, “This change was made because the potential tropical cyclone poses a threat of bringing tropical storm or hurricane conditions to land areas within 48 hours.”

To more readily communicate severe weather risks with the public, NHC now regularly releases colorful graphic maps that highlight what they call the “earliest reasonable and most likely arrival time of tropical storm force wind,” as well as showcase better ways that communicate a specific storm’s possible track.

Ross Dickman, the Meteorologist-in-Charge for the National Weather Service’s New York office, said the changes made after Sandy were significant – and they are a direct result of the storm’s meteorological uniqueness.

“I do believe Sandy triggered these changes,” Dickman stated. “In fact, one of the things the NWS does is go back to look at these storms and perform a service assessment of what went well, what do we need to improve, and how can we do things better.”

Chief among them was ensuring that the warning system was as nuanced as the storms they profile, and that communication is better between the various weather prediction agencies.

“When the NHC continues to carry on a post-tropical system, it does provide a lot of clarity in terms of communication,” Dickman said, referring to the jurisdictional changes. “The flow of information is by far superior compared to when you hand it off to another entity or office.”

Thanks to the new forecast graphics, whose creation was prioritized alongside the warning structure shifts, Dickman believes that the weather agencies are now much better equipped now.

“A picture is worth a thousand words,” Dickman said of the new maps that were developed. “Most people would agree they are helpful. Any way we can help people visualize the impact, that’s the key.”

In the wake of Sandy, both the National Hurricane Center and National Weather Service have worked on improving their forecasting methods. This image shows predictions for Hurricane Jose, in 2017. (Photo Source: National Weather Service)

But the years since Sandy struck have been especially unkind weather-wise, and in the future they’re expected to get worse.

In August 2020, the winds of Tropical Storm Isaias left more than 420,000 PSEG Long Island customers without service in their wake. The following year, Hurricane Henri triggered the region’s first hurricane warnings in a decade. As its impact loomed, Henri – in a move that was the direct opposite of what happened with Sandy – veered further east than forecasters had initially expected, and Long Islanders could let out a collective sigh of relief. Merely days later, the post-tropical remnants of Hurricane Ida tore across New Jersey and the City, causing forty-three deaths and a crippled transportation network thanks to the system’s drenching unrelenting rains. Apartment basements were flooded to fatal levels and underpasses on our area’s highways turned into deadly water hazards.

Extreme rainfall is becoming a more common feature of cyclones, and the flooding risks are slated to compound in the coming years. In fact, a recently published study of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season by Stony Brook University found that hourly hurricane rainfall rates were up to 10 percent higher compared to previous years.

Dickman explained that the NWS is now working with emergency agencies to better communicate the risks posed by flash floods.

“We’re working to revamp the flash flood emergency plan,” Dickman said. He stressed that a tiered approach is being developed to help the public differentiate between a typical summer thunderstorm and a catastrophic flooding emergency from the next Ida. “We’re always looking at ways to improve the messaging.”

It would be too simple to simply say that climate change is directly causing these storms, but global climate shifts are definitely amplifying their worst traits. Sea levels are now higher than they were when Sandy hit, and the waters of the northeastern Atlantic are measurably warmer.

“It’s not a direct one-two (punch), but all those other factors come into play,” Allen said.

And these warmer ocean waters point to an increased likelihood that severe weather will impact Long Island in the years ahead.

“At one time, with the exception of the ’38 storm due to that system’s speed, every tropical system that hit Long Island would be at a weakening stage because water temperatures can’t sustain it,” Allen explained, noting that a hurricane would require 85-to-95-degree water for a prolonged period before it could develop into a significant storm like Hurricane Ian, which slammed into Florida’s west coast in September.

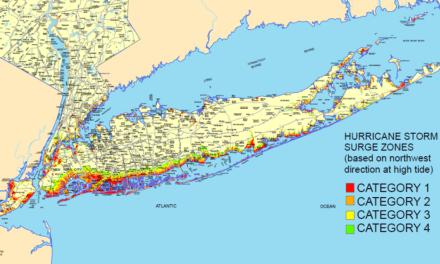

Although the chances of Long Island getting hit by a Category 4 or 5 storm is practically nil at this point in time, Allen noted that water temperatures in the Northeast during the summer months frequently reach 75-to-80 degrees.

“My fear is that you’re going to sustain a stronger hurricane up here,” Allen said. “It may not be a Category 4 or 5, but you can sustain a Category 1, 2 and possibly even a 3 much easier than you could a few decades ago.”

We saw the damage Sandy left behind a decade ago—and that was merely a “super storm,” not a full blown hurricane. Indeed, the worst is yet to come.

Richard Murdocco is an award-winning columnist and adjunct professor in both Stony Brook University’s public policy graduate program and School of Atmospheric and Marine Sciences. He regularly writes and speaks about Long Island’s real estate development and storm resiliency issues. Follow him on Twitter @thefoggiestidea. You can email Murdocco at Rich@TheFoggiestIdea.org.