The following op-ed was published in the Tuesday, March 29, 2022 edition of Newsday on page A21. You can read the original here.

BY RICHARD MURDOCCO

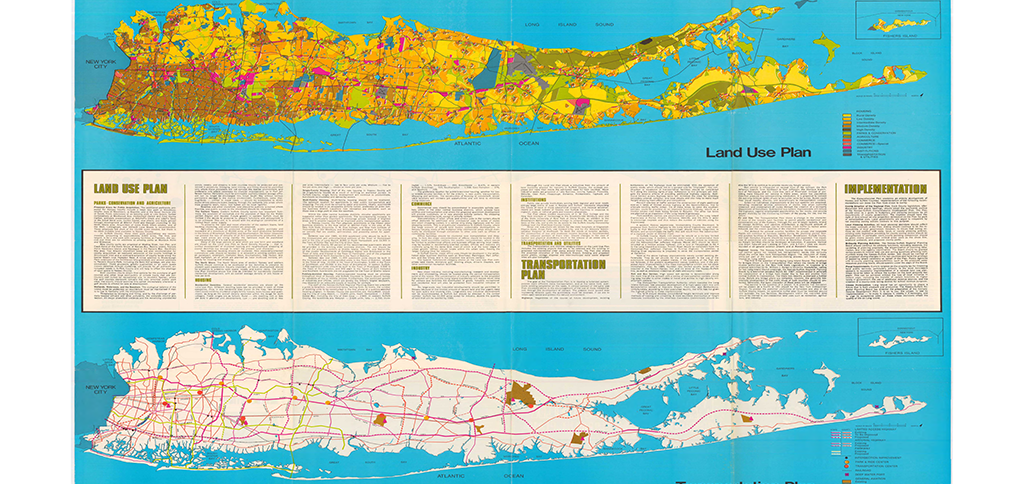

Lee Koppelman’s legacy is not found within the numerous leatherbound plans and colorful maps he crafted throughout his distinguished career.

Rather, it can be experienced from the scenic vistas of Long Island’s East End, where farmland stretches to the horizon thanks to his protection of open space, or whenever a child drinks clean potable water from the tap due to his groundbreaking studies of development and its impact on water quality.

And by applying the principles that he embedded within his plans more than a half-century ago, our region’s future can be more sustainable and prosperous.

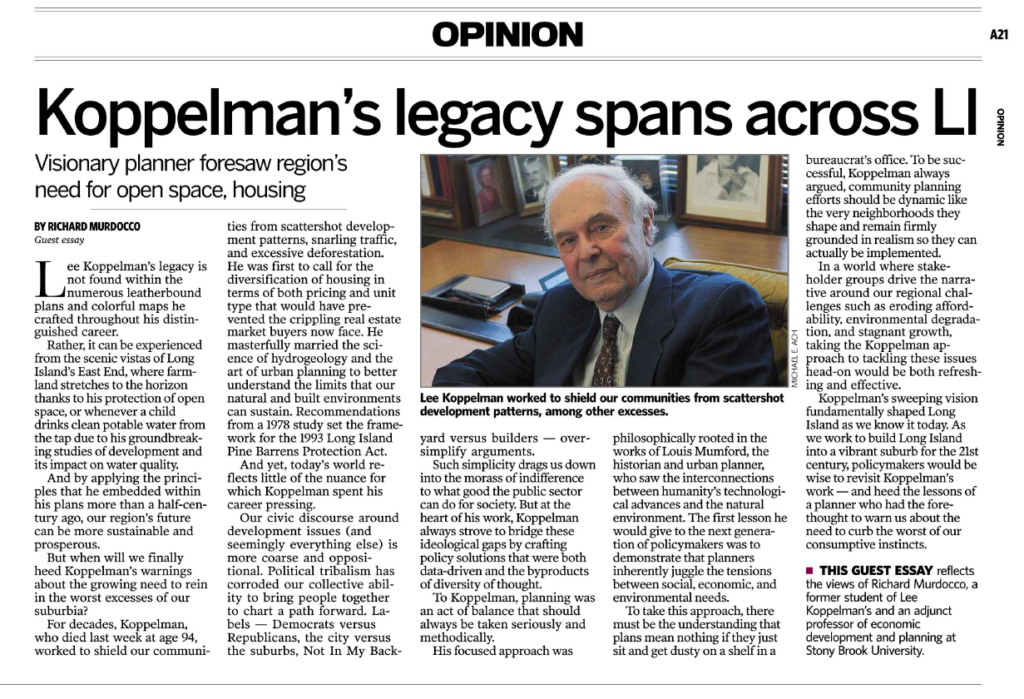

Pictured: Dr. Lee Koppelman, right, teaches his class at Stony Brook University on the evening of May 11, 2006. (Photo Credit: Thomas A. Ferrara, Newsday)

But when will we finally heed Koppelman’s warnings about the growing need to rein in the worst excesses of our suburbia?

For decades, Koppelman, who died this week at age 94, worked to shield our communities from scattershot development patterns, snarling traffic, and excessive deforestation. He was first to call for the diversification of housing in terms of both pricing and unit type that would have prevented the crippling real estate market buyers now face. He masterfully married the science of hydrogeology and the art of urban planning to better understand the limits that our natural and built environments can sustain. Recommendations from a 1978 study set the framework for the 1993 Long Island Pine Barrens Protection Act.

And yet, today’s world reflects little of the nuance for which Koppelman spent his career pressing.

Our civic discourse around development issues (and seemingly everything else) is more coarse and oppositional. Political tribalism has corroded our collective ability to bring people together to chart a path forward. Labels — Democrats versus Republicans, the city versus the suburbs, Not In My Backyard versus builders — oversimplify arguments.

Such simplicity drags us down into the morass of indifference to what good the public sector can do for society. But at the heart of his work, Koppelman always strove to bridge these ideological gaps by crafting policy solutions that were both data-driven and the byproducts of diversity of thought.

To Koppelman, planning was an act of balance that should always be taken seriously and methodically.

His focused approach was philosophically rooted in the works of Louis Mumford, the historian and urban planner, who saw the interconnections between humanity’s technological advances and the natural environment. The first lesson he would give to the next generation of policymakers was to demonstrate that planners inherently juggle the tensions between social, economic, and environmental needs.

To take this approach, there must be the understanding that plans mean nothing if they just sit and get dusty on a shelf in a bureaucrat’s office. To be successful, Koppelman always argued, community planning efforts should be dynamic like the very neighborhoods they shape and remain firmly grounded in realism so they can actually be implemented.

In a world where stakeholder groups drive the narrative around our regional challenges such as eroding affordability, environmental degradation, and stagnant growth, taking the Koppelman approach to tackling these issues head-on would be both refreshing and effective.

Koppelman’s sweeping vision fundamentally shaped Long Island as we know it today. As we work to build Long Island into a vibrant suburb for the 21st century, policymakers would be wise to revisit Koppelman’s work — and heed the lessons of a planner who had the forethought to warn us about the need to curb the worst of our consumptive instincts.

This guest essay reflects the views of Richard Murdocco, a former student of Lee Koppelman’s and an adjunct professor of economic development and planning at Stony Brook University.