The following are quick hits of editorial analysis from The Foggiest Idea on the local and regional developmental issues that matter. For more, be sure to LIKE TFI on Facebook.

By Richard Murdocco

October 29th, 2020

As reported by the New York Times, the long running saga fight over the development of a BJ’s Wholesale Club on a 28.3 acre wetland site in Staten Island may be coming to an end despite years of protests against the proposal from local residents.

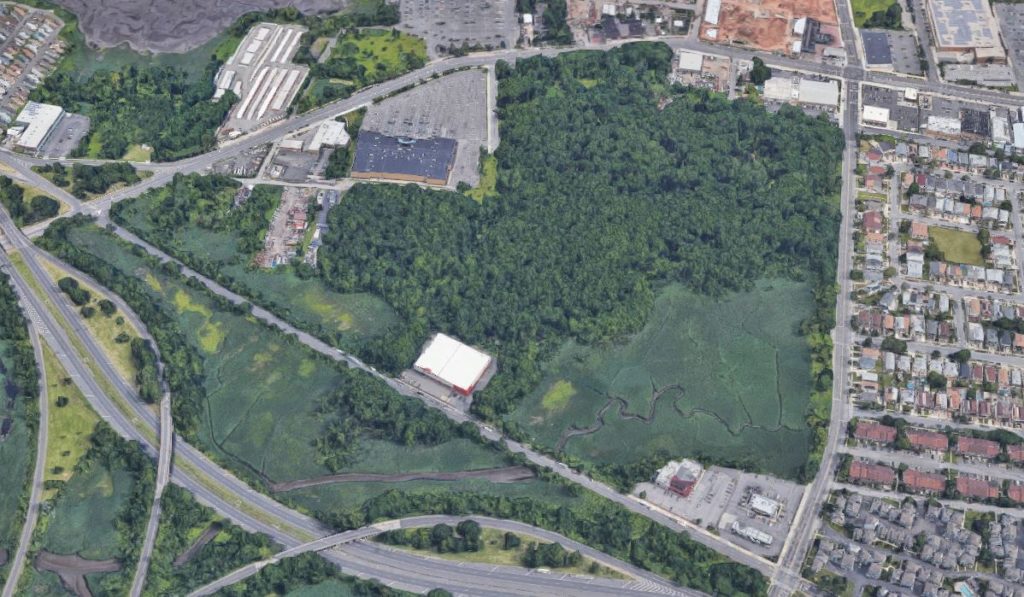

Pictured: An aerial image of the 28.3 acre development site on Staten Island where a BJ’s Wholesale Club has been approved. Roughly 18 acres of wetlands would be cleared when the store is built. (Photo Credit: Google Maps)

Those who live nearby claim that the waterfront marshes slated for development protect their homes from floodwaters driven by storm events and climate-change. In a 2017 report on the matter, the City Planning Commission found that “…the proposed development footprint is wholly located outside of the regulated wetland areas,” and went so far as to note that the project would be environmentally beneficial compared to legally-allowed alternative approaches due to the application’s slated preservation of nearly 11 acres of marshes.

After years of back and forth with city and state officials, the project, which would clear roughly 18 acres of wetlands, was formally allowed to proceed by New York State in 2019.

The Foggiest Idea‘s Take: It is clear from this example that the lessons of superstorm Sandy, the post-tropical cyclone that ravaged numerous waterfront communities across the New York metro region on this date back in 2012, are still not being heeded by policymakers.

Staten Island was one of the hardest hit areas by the storm within New York City, and the need for additional protections for vulnerable areas of the borough are growing as hurricane seasons in the northeast worsen.

Both James Oddo, Staten Island’s borough president, and Debi Rose, the area’s City Council representative, should work together to press for stronger protections for smaller pockets of wetlands citywide. Currently, New York State law fails to protect parcels of freshwater wetlands that are smaller than 11 acres. Most of the wetlands found within urban areas fall into this unprotected category. Clearly, gaps in the law exist. “I did emotionally understand the community’s arguments — I lived through Sandy,” Oddo told the Times. “But legally, where would I stand if I wanted to oppose it?”

Having both Oddo and Rose work to fill the gap between state and local protection of these critically-important wetland properties is the right place to start to ensure more coordinated planning in the face of climate change across the New York metropolitan region.

AFTER A PANDEMIC LULL, TRAFFIC WOES RESUME ACROSS LI:

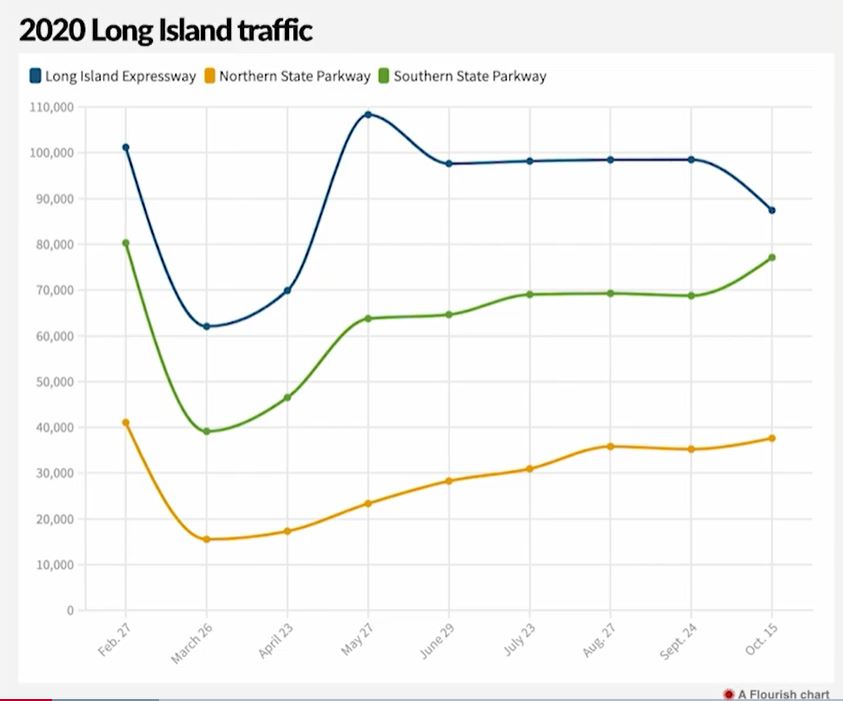

After traffic levels plunged during the early days of the pandemic this spring, Newsday is reporting that vehicle volumes have nearly fully recovered back to their pre-pandemic levels across Long Island. Meanwhile, transit revenue continues to hurt as LIRR ridership remains 70% lower than it was a year ago.

The Foggiest Idea’s Take: With more people hitting the roads in their personal vehicles and less opting to ride mass transit, traffic congestion is not only here to stay but is likely to be even worse than it was before the coronavirus hit. Thanks to the fact that most of the roads and highways in Nassau and Suffolk counties are woefully outdated and cannot handle the traffic that already travels on these routes as it is, any additional demands that are placed upon the regional road network won’t easily be absorbed.

Unfortunately, it would seem that there are no easy solutions to solving the region’s traffic woes – either policymakers must have the political fortitude to expand the capacity of existing roads that are bound by countless neighborhoods and businesses, or a series of alternative transportation options have to be planned, financed, and adopted regionwide.

Really appreciate your insight into this problem on Staten Island. We are NYC’s poster child for the damage done by Sandy and yet we will lose the protection the Graniteville Wetlands Forest gave us. Please take a look at this site, below. Thank you.

http://www.sicwf.org