The following was published exclusively on The Foggiest Idea on January 30th, 2019. Want to support The Foggiest Idea’s award-winning coverage? Click here.

By Richard Murdocco

Just when we think we have a handle on one major problem affecting our drinking water supply like nitrogen run-off, other serious concerns rise to the surface. From Westhampton Beach to Bethpage and Farmingdale, pollution from decades past haunt our present. Taking the form of discarded opioids, fire-retardant foams and chemical solvents, to name some of the most serious, these substances collectively combine to do harm to future generations of Long Islanders if left untreated.

Perfluorooctane sulfonate (or PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (or PFOA) have increasingly been detected in Long Island’s water supplies although the Environmental Protection Agency only recently began requiring tests for these chemicals after recognizing the growing danger they pose to human health. They have been traced to their use in fire-suppression foams, industrial manufacturing and other practices. Even though their use was phased out by manufacturers in the early 2000’s, the toxic legacy these foams have left behind won’t quickly fade away.

In 2013, the Suffolk County Water Authority, which is responsible for the majority of public water suppliers in the county, began detecting PFOS and PFOAs in public and private supply wells near Francis S. Gabreski Airport in Westhampton. The airport, which is almost across the street from BOCES-Westhampton Beach Learning Center, was declared a Superfund Site in September 2016. SCWA claims it promptly took corrective actions. But the chemicals have been detected in groundwater wells in Yaphank, Calverton, East Hampton Airport, Brookhaven National Lab and MacArthur Airport in Islip.

Gabreski Airport was declared a Superfund site by the NYSDEC in September 2016 due to the presence of PFOS. Source: NYS.gov

“The Suffolk County Water Authority has proactively tested for the presence of PFOS and PFOA in the wells south of Gabreski Airport since 2013, and regulators have used information we’ve provided to establish a health advisory,” said Tim Motz, director of communications at SCWA in a prepared statement in response to an article in 27east in November 2016 that raised questions about the agency’s timing.

“Prior to the advisory, we addressed detections of these chemicals by either removing wells from service or blending water sources,” Motz said. “We now have treatment in place to remove any detected levels of these chemicals from the water supply and, as a result, we’ve had no further detections.”

But PFOS and PFOAs aren’t the only toxins to surface in recent years.

A nationwide study done in 1999 and 2000 by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) found low levels of pharmaceutical drugs such as antibiotics, hormones, contraceptives and steroids in rivers and streams.

The issue eventually hit Long Island in 2005, when a USGS study first detected trace levels of pharmaceutical drugs in 28 of 70 water samples collected from Suffolk groundwater wells. Governmental agencies continued their research and found that the widespread practice of flushing unwanted meds was the main source of drugs entering Long Island’s waters. Years later, Citizens Campaign for the Environment, a Farmingdale-based non-profit environmental advocacy group, followed up with another high-profile report of their own in 2013 that raised similar concerns as part of larger protective efforts.

Since the CCE report, public awareness about the issue has continued to rise.

“Unquestionably it’s an emerging threat we don’t understand quite yet,” said Kevin McAllister, founder of the Sag Harbor-based environmental group Defend H2O.

“Pharmaceuticals and other emerging contaminants represent a defined challenge for the region’s water quality,” Bob DeLuca, president and CEO of Group for the East End, a non-profit advocacy organization based in Bridgehampton, told The Foggiest Idea. But he called the issue “fairly small” compared to curbing the impacts of, say, nitrogen in wastewater.

Removal of nitrogen in groundwater has been the county-wide focus of its water quality efforts, which culminated in two successful local referendums passed on Jan. 22, 2019 that resulted in voters giving the greenlight to proceed with multimillion dollar projects to expand sewers in Mastic, Shirley and the Babylon area. A similar proposal for Great River was readily denied by voters with strong turnout.

In Mastic, Shirley and Babylon, the annual cost to homeowners would be $470 and $532 respectively. In Great River, many residents cited the proposed $755 annual cost for the new project as the reason why they voted it down.

After the defeat, Suffolk County is considering other ways to use the $26.4 million that was proposed for the impacted area. Even with sewers, which primarily protect against nitrogen from wastewater, other measures will still be necessary because PFOS, PFAS, and 1,4-Dioxane are decidedly nastier and require specialized treatments.

Unfortunately, much more remains to be done, both large and small, to restore our drinking water to its pristine condition. And while none of what’s needed is particularly cheap, low-cost actions can help.

To that end, DeLuca does believe that prescription take-back programs at major pharmacy chains and area hospitals are beginning to make a difference in eliminating the threat these discarded drugs pose.

“There is no silver bullet here,” he said, “but early awareness and improved management practices can and will have a material impact on the levels of these pollutants entering the environment.”

A flyer highlighting drug take-back program sponsored by Suffolk County in June 2015. Source: Suffolk County

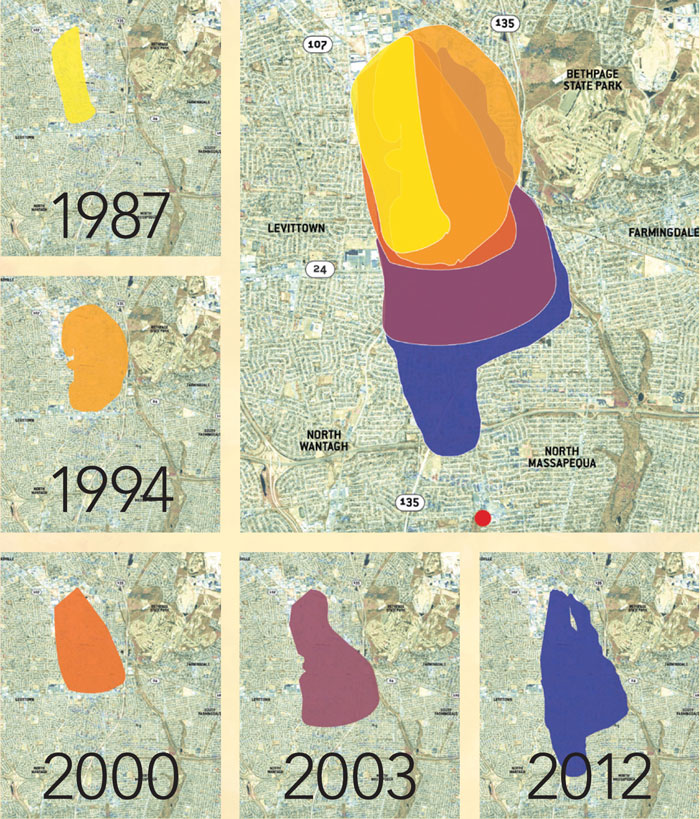

Meanwhile, 1,4-Dioxane, a compound found in paint strippers, solvents and household products, is also on the radar for policymakers to curb, thanks to its high-profile presence at sites like the former Grumman facility in Bethpage. There, a growing plume of contaminated groundwater has been grabbing headlines and stoking fear of what lurks beneath.

While contaminants from firefighting foams and pharmaceuticals can be treated with existing methods and preventive action, removing 1,4-Dioxane is considerably more complex and expensive. New York State has committed $150 million to remediation efforts in Bethpage. The state has also directed its environmental agencies to hold both Northrop Grumman and the U.S. Navy accountable.

Given Long Island’s geologic conditions, contamination of drinking water was all but inevitable as industry in the region blossomed with little regard – or understanding – of the dynamics of groundwater.

“As a region, Long Island faces the challenge of maintaining an exceptionally large human population situated on a landmass that is highly vulnerable to water quality contamination from many sources,” DeLuca explained. “Unfortunately, the footprint we have left on the quality of these precious water resources over the years is substantial.”

In response, the Long Island Commission for Aquifer Protection, a New York State advisory panel comprised of academics, health and environment officials, and water providers recently recommended tough new drinking water standards for the toxic cocktail of contaminants. Their recommendations serve as the first step towards establishing concrete policy. After a public comment period, officials say that final implementation is likely this spring or summer.

If enacted, the proposed limits would be the most stringent regulations in the nation.

Residents may welcome the imposition of strict regulation but the suppliers of our drinking water may not feel that way if they’re stuck with the tab.

“What is the environmental and financial burden with the clean-up?” said Ty Fuller, Lead Hydrogeologist with the Suffolk County Water Authority and chairman of the Long Island Water Conference, which includes major water suppliers, both public and private, on Long Island, in a conversation with The Foggiest Idea. “We’re talking about compounds that are not easily removed with conventional clean-up.”

Fuller warned that costs could skyrocket if tougher treatment measures become necessary as stricter rules are imposed. The likelihood, in turn, is that water providers would have to pass the elevated costs to the residents they serve.

“New York State is considering levels that would be costly to water suppliers,” he said, adding that making the Navy and Northrup Grumman pay their share makes sense. “Assign culpability to get polluters on the hook for the mess they created,” Fuller stated.

State officials peg the annual costs of curbing PFOA and PFOS across the state at $855 million in capital costs and $45 million a year annually. The DEC estimates that 23 percent of public wells across New York contain PFOA or PFOS. To begin attacking the 1,4-Dioxane issue, officials have estimated $318 million in capital costs, adding that roughly $13 million in recurring annual costs would be necessary. A majority of the money would go towards treating wells on Long Island – the epicenter of the 1,4-Dioxane problem in New York.

A graphic showing how a plume of contamination from Northrop Grumman’s plant in Bethpage has grown over the years. Source: NYS DEC

“When you consider the cost—and there is an extreme amount—it affects everyone,” he said. “New York State has had to invest an extraordinary amount, which hasn’t been seen in decades.”

For more manageable threats to groundwater such as pharmaceutical pollution, Fuller said that agencies like the United States Geological Survey have already taken action. They have started monitoring programs to look at the impacts of meds on wastewater, and determine just how effective existing technology like carbon filters are at remediation.

“At least right now, we’re doing focused monitoring,” Fuller said.

Looking on the bright side, Fuller said that public awareness of these issues is “absolutely better” than it’s ever been. In addition, he believes that regional cooperation has improved drastically and that it will help streamline the collection of water-quality data around the Island. Eventually he hopes to see it all compiled in a single, centralized location.

Still, between the costs of expanding sewer networks for nitrogen removal and the necessary treatments for 1,4-Dioxane, pharmaceuticals and PFOS/PFOAs, Long Island’s elected officials find themselves staring into an abyss. They know that the region must spend the money needed to address a growing health crisis – but how?

“Get polluters on the hook,” Fuller said. “The residents of Long Island are not responsible for their contamination of their water supply, but they are being asked to bear the financial burden of the clean-up.”

Here we are, almost two decades into the 21st century, and we still have no idea what it will cost to rectify years and years of neglect of our precious drinking water supplies. But we can’t afford to do nothing, can we, if we still want to call this Island home.

Richard Murdocco is an award-winning columnist and adjunct professor in Stony Brook University’s public policy graduate program. He regularly writes and speaks about Long Island’s real estate development issues. You can email Murdocco at Rich@TheFoggiestIdea.org.

One solution is to stop the high-rise, high density, mixed use projects. Stop leveling hundreds of acres of wooded areas. The environmentalists and politicians are only concerned with the environment when it suits them. Follow the money.

While I agree that polluters should be held accountable, part of the problem is that some of this contamination (like Grumman) occurred before anyone knew what the consequences of use and/or dumping of these chemicals would be. There are literally over 80,000 chemical compounds in use today that are not tested for toxicity to animals or humans before being put to use. The EPA does not require it. It is only when problems or sickness occurs do they start testing. Then it takes many years for the EPA to do anything to regulate or ban that chemical. Then the manufacturer/polluter comes up with a very slightly different compound that does basically the same thing. As long as its make up is different, it is legal for them to use it. Then many years go by before THAT particular compound is flagged. It’s just nuts. Every compound should be required to be tested for toxicity BEFORE it is put into use. But then the financial burden will be placed on the manufacturers, and God forbid that should happen. The companies will either make less profit (not going to happen) or they’ll pass on the increased cost to the consumer (Oh no! More expensive goods!) Or, as noted in this article- we the people will bear the burden in increased water rates due to increased cost of treatment, or we’ll pay the doctors, the hospitals and health insurance companies, or with our very lives.