The following originally appeared in the July 2018 issue of Long Island Pulse Magazine. You can read the original here. Interested in supporting The Foggiest Idea’s award-winning reporting and analysis? Click here.

By Richard Murdocco

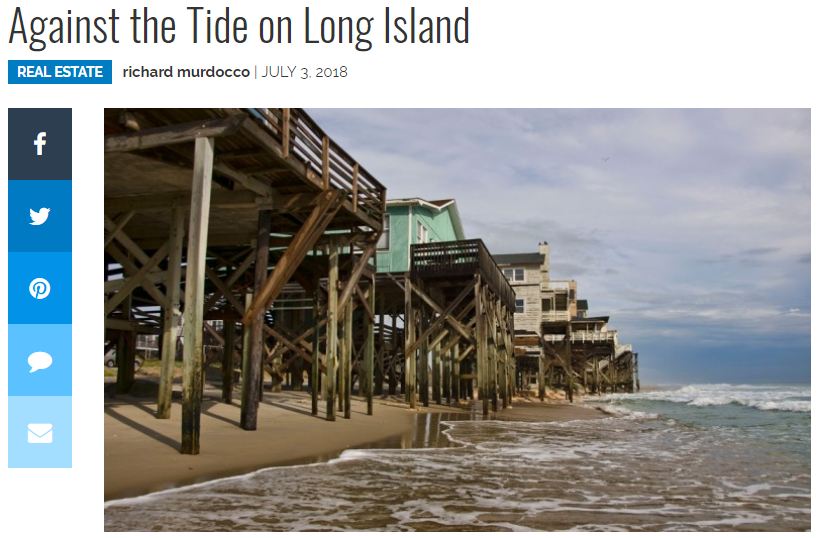

To live on Long Island is to embrace the water, and many Long Islanders cherish it enough to set down roots in a shorefront house. But a multitude of storm events that are only going to get worse threaten the expansive coastlines around our Island to be swept away with the tide. As the sand washes away beneath them, can anything be done to protect the multimillion-dollar homes that line Long Island’s fragile coastline?

Residents and municipalities have artificially braced the region’s coasts for decades, but attitudes are shifting. Now more government officials are open to letting nature take its course. “Coastal communities across Long Island are just beginning to see the effects of sea level rise,” said Kevin McAllister, founder of the Sag Harbor-based environmental group Defend H2O, who added that the trend of allowing encroaching tides seems to be accelerating—much to the concern of policymakers and homeowners. In East Hampton, the town is considering moving threatened businesses on Montauk’s coast further inland, allowing the land to eventually be swallowed by the ocean. After the series of successive nor’easters that hit this past winter, the municipality is weighing the costs against the benefits of fortifying the coasts.

Defend H20 advocates for natural shoreline protection and restoration. “Unfortunately, the general response has been to armor the shoreline with hardening projects,” McAllister said. “The impacts of this approach have resulted in the inevitable disappearance of the fronting shoreline anyways.”

The risks are beginning to impact the attitudes of property owners. In turn, the market is reacting.

“There are definitely safer spots than others,” said one broker with more than 20 years’ experience selling East End waterfront homes, who declined to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue with buyers—and sellers. The broker said there has been a “flurry of activity” in high-risk storm surge and erosion-prone areas such as Gerard Drive in East Hampton. Nestled between both Gardiner’s Island and Bay, a spate of homes on the peninsula hit the market in spring of 2018. “I’ve had sellers say they don’t want to deal with the anxiety of nor’easters anymore.”

Such matters aren’t merely an issue for the shorelines of eastern Suffolk County—further west in the small villages of Nissequogue and Head of the Harbor within the Town of Smithtown, local officials are grappling with how to best corral their coastal issues. Richard B. Smith, the Village of Nissequogue’s mayor since 2001, has ample experience on the matter. “This has been going on since Long Island was created,” he said. Smith added that estimates are that the North Shore loses anywhere from one foot to a foot-and-a-half of land each year. “It’s ever-present.”

As a result, Smith said that Nissequogue is being more open-minded when it comes to the protection of the property of residents. “The village has consistently sided with homeowners. I think that as a local government, we are charged with looking out for the interests of our residents by protecting their property.” After the series of strong nor’easters hit this past winter, the issue became even more pressing for the tiny municipality, which has approved a series of hardening measures for half a dozen or so homeowners to take. The village’s approach has been that if a homeowner’s property is imperiled, they can enact erosion control measures such as the renovation of an existing bulkhead. “Without protection, we will eventually lose one hundred feet or so of land by the next century—if not more. These measures slow erosion down, but it’s up to mother nature.”

Lawrence Swanson, an interim dean of the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University, is concerned that waterfront properties in both Nissequogue Village and nearby Head of the Harbor, where Swanson was also a former trustee, are under threat—and hardening makes matters worse. “There are hardening measures such as sea walls that if done on a property-by-property basis, will have major downstream consequences that make the problem even worse,” he said. “If we want to maintain the Island, we can’t make one part of that complex system static.”

To Swanson, both local governments and the real estate industry must take action soon. “Government should develop and enforce zoning laws. Setbacks are essential, as are regulations limiting clearing by the edge of the bluff and certainly on the bluff,” he said, and noted that in some hard-hit areas, anywhere from two-to-three feet of coastline can be lost per year.

Private industry must also do their fair share. “One of the most important problems comes from the real estate business,” Swanson said. “They are not being straightforward with potential buyers about sea level rise. We can’t expect them to be experts on climate, but they are often not answering questions about risk.”

Despite these significant risks in the coming decades, the power of waterfront living seemingly supersedes all else—at least for now. “I believe that in the short term, individuals who can afford coastal properties will believe that they can do whatever to protect their property, and if not, they will litigate,” Swanson said. Smith agreed that the threats will do little to deter homebuyers. “It’s not a new issue, and as long as the properties aren’t subject to flooding, demand will continue to remain strong.”

Regardless of market forces, Swanson feels that in the long run the fight against erosion is a losing proposition. “While some may think that entombing the Island is the best thing to do, the fact is such action will diminish, if not eliminate, the values we consider to be important to our environment and economy.”

Richard Murdocco is an award-winning columnist and adjunct professor in Stony Brook University’s public policy graduate program. He regularly writes and speaks about Long Island’s real estate development issues. More of his views can be found on thefoggiestidea.org or follow him on Twitter @thefoggiestidea. You can email Murdocco at Rich@TheFoggiestIdea.org.