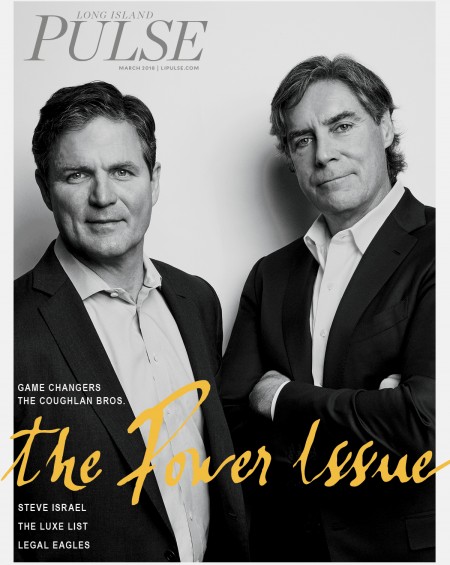

The following is an edited version of a piece that was first published as cover story for the March 2018 edition of Long Island Pulse Magazine. You can read the original version here.

For decades, planners on Long Island have debated diversifying the region’s housing stock from the cookie cutter, single-family homes of Levittown into something more—a rich tapestry of options that accommodates multi-generational needs and desires.

For the better part of those decades there’s been little progress on this front. A lack of political will to think outside the box and a market that pushed for single-family homes stalled even the best-laid plans. But tides are turning. Suburbia is transforming in a wave of growth that hasn’t been seen since the days of Moses (Robert) or Levitt (and Sons). There’s no denying the powerful forces behind this transformation—many are driving the modern housing revolution—and a few stand out not simply for their ability to get zoning changed or break ground, but for something more.

Three forces in particular have had a resonant impact on the developmental climate of Long Island that is likely to be felt across future generations. Sometimes it’s decades-worth of policy-oriented successes that laid the groundwork for new approaches. Other times it’s a grassroots economic philosophy that wins the day. But the sum of the parts isn’t measured exclusively by units occupied or density reached. It’s the legacy such efforts leave behind.

The cover of the March 2018 edition of Long Island Pulse Magazine.

Trailblazer

When sitting across from Mitch Pally, it’s easy to tell why he’s so effective in his business. He has served as the chief executive officer of the Islandia-based Long Island Builders Institute since 2010, exuding the type of charm and influence that make it evident he is the authority on Long Island development. As well he should—he’s been involved with civic and policy matters in Nassau and Suffolk Counties since his first stint in public service with the New York State Legislature in 1975.

Today, Pally’s roles are varied. He is the guiding force behind LIBI, an organization dedicated to advancing the region through economic growth via development while staying mindful of environmental conservation. LIBI members build the majority of the 5,000-plus homes constructed on the Island each year—all to the tune of roughly $1 billion dollars annually.

In addition to his role with LIBI, Pally currently sits on the MTA Board of Directors, a position he has held since 2005 when then-county executive Steve Levy first appointed him. Prior to that, he worked for 21 years as vice president of government relations for the Long Island Association, the leading business organization in the region. His work with the LIA set the stage for his work at LIBI. Throughout his career, Pally has believed real estate issues are a key way of understanding Long Island’s growth. While at the LIA, Pally worked with environmentalists to help shape the NYS Pine Barrens Act. The 1993 piece of legislation set aside more than 100,000 acres of pine forest that stretches from eastern Brookhaven township through Southampton. The effort to preserve the Pine Barrens “was when we started getting involved with the detail-oriented aspect of where development should occur. That was when the awareness of what development means for Long Island became paramount.”

The dynamic of conservation versus construction is one that persists. “In many areas on Long Island, real estate development is looked at as an inconvenience,” he stated, citing residents’ frequent complaints about the traffic and tax impacts of development. “In many other parts of the country, it’s seen as a reward…It takes lots of money, lots of patience and perseverance and an understanding of the governmental process [to be a successful builder on Long Island].” It’s for this reason that there are few national homebuilders with a presence in Nassau and Suffolk Counties—they simply gave up and left town. “If you don’t have those three attributes and an understanding of how the government process works on Long Island (from a real estate point-of-view), you don’t have a chance.”

Despite challenges, Pally paints an optimistic picture of an interconnected region that is now growing up instead of out. “I think we’ve managed to change the perception of—not all Long Islanders, but many—toward the different types of development projects that are essential to the 21st century, such as mixed-use, multifamily. The changing demographics and needs of the community are pushing the developers in that direction.”

Change Agent

The unincorporated hamlet of Riverside, nestled between the towns of Riverhead and Southampton, doesn’t easily relate to the glitzy veneer of the Hamptons. Over the years, the hamlet has seen its share of hard times but Plainview-based Renaissance Downtowns believes the area is a diamond in the rough.

Sean McLean and Ryan Porter serve as co-CEO of Renaissance Downtowns and are passionate about the company’s philosophy to create “thriving and successful communities.” The attitude permeates during any real estate-related conversation with McLean, who speaks about development matters with a sense of urgency. The company’s dedication to Riverside isn’t surprising. Renaissance Downtowns has bet its future on the power of such development-driven revitalization, proposing major projects in Huntington Station, the Village of Hempstead and pockets of Glen Cove.

McLean believes developmental efforts on Long Island should have a higher calling. “Regardless of being known for downtown redevelopment or going into places that have issues that we need to work with the community to fix, our core values are set in creating a better place than exists today.”

To effectuate their brand of change, Renaissance seeks out municipalities that are ready to embrace it. “The number one driving force is that we have a real partner in both the municipality and the community that wants change. We don’t go into these communities knowing what that change is exactly.” Renaissance opens local offices and goes through the planning process to determine how to best build and invest depending on the area. Once a community understands growth and wastewater treatment, they are more willing to support the plans. In Riverside, where the developer is looking to build 2,267 housing units, including a combination of affordable housing and market-rate apartments alongside professional, office and retail spaces, McLean said the residents and officials are onboard with what they’re trying to accomplish.

Even with policymakers’ support McLean pushes the boundaries of local involvement. “We have to be willing to push government to places where they’re uncomfortable. Often, elected officials and staff don’t want the community involved as much as we like to involve them, we do try…so the community sees their ownership in the development process.”

Long Island’s future housing needs are critical in the shaping of how Renaissance does business. “We have to push local government to face the technical challenges we face as a region,” McLean said, painting a grim picture for both Nassau and Suffolk Counties if the status quo isn’t shifted. “If left unabated, even with the great strides we’re seeing around train stations and building good places like TRITEC is doing in Ronkonkoma, the jobless rate could approach 50 percent in the next decade,” he said, citing the growing number of retirees and the deterioration of the job market as contributing factors.

“As a real estate development firm, we are looking at technological advances we feel will impact the local economy. We want our developments to be ready to handle anything that comes with the national and international economy.” To do this, Renaissance offers “significant flexibility in the entitlement packages” in each of their efforts to ensure that when markets and technology shifts, their zoning is “100 percent ready to stay resilient environmentally and socially.” In short, they seek flexible zoning that evolves alongside the market.

Even though Renaissance is on the cutting edge of the modern development spectrum, for McLean it all comes back to the residents. “We really try to give a voice to the people in the community and build on the character of the people that are there.” The opportunities they’re trying to create aren’t exclusive to Renaissance either. The company is welcoming of additional developer participation on their projects. “It’s not just that we’re building those projects. We invite the world to invest alongside us.”

Power Players

Aside from William Levitt, it’s likely that no other developer on Long Island has as much name recognition as TRITEC Real Estate. Brothers Jim and Bob Coughlan serve as co-principals of the East Setauket-based development firm and have become known for transformative projects in a region that isn’t always accommodating of growth.

The company began in Manhattan in 1986 and quickly shifted focus to Long Island a few years later. (Their third brother, Dan, heads TRITEC’s D.C. office and their father, Robert, is Chairman Emeritus of the Board, as well as the steward of the company’s investment banking activities.) The Coughlans grew up in Hauppauge, giving them a familiarity with the local landscape. Their first major project in the area was the Stony Brook Technology Center in the early 90s. The brothers transformed the would-be industrial park into medical and office space. Today the site is a regional powerhouse for medical research and job creation.

Since Stony Brook, the epicenter of the company’s development has been within the once unassuming and economically struggling Patchogue Village. Smart growth advocates from across the country celebrate its 290-unit New Village project on Main Street. It was designed to enliven the streets of Patchogue by providing retail, restaurants and civic amenities such as a village green. “They sat with the community and continued to look at us as a community. All without losing the sense of who we are,” said Paul Pontieri, the mayor of the Village of Patchogue.

Since being elected in 2004, Pontieri has been addressing the village’s challenges by working with companies like TRITEC to map out a community-centric approach to development. “I’ve spoken with mayors of Amityville, Port Jefferson and Lindenhurst, and their experiences with them were all the same,” Pontieri said. “TRITEC spoke to historic groups, the community groups like the Chambers of Commerce, Lions or Rotary Clubs, and discussed the vision they had for their communities. TRITEC didn’t just listen to what we were saying, they accepted it.”

The Coughlans believe a developer’s success is predicated on the ability to be dynamic, in addition to selecting smart sites. “We only go where we’re wanted,” Bob said, saying it’s a motto of sorts for the company. “If we can get 85-to-90 percent of the people in favor of a project that we’re proposing and we know we’re wanted, then we’re willing to invest the capital. This often times requires making changes to the projects as needed after public hearings.”

Much like Pally, Jim believes Long Island’s unique environment creates a compelling proposition for builders. “Even though the demographics of income and education are similar to other markets, it’s still very different due to its colloquialism,” he said. “At the end of the day, it’s an Island and you have to get on and off it, primarily at the western end. This creates a different mindset of how the market functions. A [New Village] wouldn’t have happened eight or nine years ago,” he added, noting transit-oriented options weren’t readily considered then.

Diversity in housing and developments with a wide range of bells and whistles are projects that have come to the forefront—these are areas where TRITEC excels. “You have to be a jack of all trades, or coordinate a lot of skills…to be in the development business,” Bob said.

Their coordination has paid off, especially since TRITEC’s projects are as diverse as they are impactful. In the Village of North Hills, the company’s partnership with Manhasset-based Castagna Realty helped create DealerTrack’s new 230,000-square-foot headquarters, which opened in July 2017. DealerTrack, a provider of dealership financing technologies, is one of the largest companies in the region and their new 10-acre home has been a plan in the making for nearly 14 years. The facility houses around 600 employees and boasts indoor basketball and volleyball courts, a walking trail and more 21st-century corporate amenities.

After working with New York State to secure tax breaks, the company has committed to remain in North Hills for at least 17 years due to a long-term lease agreement. At the time, Jim said via released statement that the “empowering investments from both the New York State Empire State Development Corp and the Nassau County IDA” serve as examples of the successes of public investment in local economic development efforts.

Further east in Suffolk County, TRITEC’s Ronkonkoma Hub is slated to breathe life into the community with 1,450 residential units and ample retail and office space to fill the remaining acreage. Long term plans for the 53-acre project also include shuttles between the LIRR station and MacArthur, promising to elevate the Town of Islip airport to a major transport hub.

That project, whose concept has been toyed with by policymakers for decades, may become the company’s crowning achievement. But for the brothers it is no swan song. “We’re hoping to make this the best project we’ve ever done, but we’re hopeful there’s more for us to do,” Jim said.

The brothers feel the changes in the market are positive and will help Long Island businesses attract employees more easily. As the tide of public opinion continues to turn in this direction, toward multifamily, they plan to keep pace. “The developers who are out here are becoming more active,” Jim said optimistically. “Even though it can be incredibly difficult, it is actually getting easier…We’ve always been a company to embrace change and it’s going to keep happening quicker and quicker,” Jim said. “As long as we can learn faster than the changes happen, we will continue to see growth and opportunities at TRITEC.”

Richard Murdocco is an award-winning columnist and adjunct professor in Stony Brook University’s public policy graduate program. He regularly writes and speaks about Long Island’s real estate development issues. More of his views can be found on thefoggiestidea.org or follow him on Twitter @thefoggiestidea. You can email Murdocco at Rich@TheFoggiestIdea.org.

For those who believe that for decades there has been very little on the development front for planners and builders, let me educate you. Below is a list of projects from across Long Island, which is not updated, as it became too huge a task to keep up. And, for those who believe it requires much ability to get zoning changed, all I have to say is “follow the money.”High Density Apartment Developments/PENDING or APPROVED FOR Long Island

UNITS IN bold ITALICS ARE APPROVED OR BUILT

Amityville North (Greybarn) – 500 Units

Amityville (Liberty Village, Veterans Housing, (Concern for Independent Living) – 60 Units

Amityville (Artspace) – 35 plus Units

Amityville (Oak St.) – 12 Units

Aquebogue (affordable) – 30 Units

Amagansett, 531 Montauk Hwy. – 40 units

Baldwin – 142 Units Bayport – 148 Units

Bayport (Fairway Manor/Islip Green) – 260 Units (45 & 55 and over) Bay Shore – 132 Units + 55 Units Bay Shore (Maple Avenue) – 90 Units (4 story)

Bay Shore (5th Ave & Union Blvd.) – unknown

Bayville – Unknown

Bellport, North – (14 Acres) unknown

Bluepoint, The Vineyards – 280 Units (55 and over) Brentwood (Heartland) – 9,100 plus Units

Center Moriches, Vineyards at Brookfield -146 Units (55 and over)

Copiague (Great Neck Rd.) – 420 Units

Copiague (54 Railroad Ave.) – 90 Units Coram (Wincoram) – 176 Workforce Units

Cutchogue (The Heritage) – 130 Units (55 and over)

East Islip (Westbrook Village – Sunrise Hwy.) 320 units East Northport – 256 Units (Oak Tree Dairy) – (55 and over)

East Setauket – Setauket Meadows in the Woods – 100 units

Farmingdale (Cornerstone, Bartone Properties) – 39 Units

Farmingdale (Eastern Parkway) – 27 Units

Farmingdale (Fulton St., Hearthstone, Bartone Properties) – 24 Unit Townhouses Farmingdale (Jefferson Plaza) – 154 Units

Farmingdale – (Main St.) – 26 units + 14 units (Staller Associates) Farmingdale – 53 Units Farmingdale Village (Bartone Plaza) – 115 Units

Farmingville, the Arboretum – 292 Units Farmingville, The Bristal – 145 Units (55 and over)

Floral Park – (Koenig) – undetermined at this time

Fort Salonga Indian Hills Golf Course – 108 Units (55 and over)

Freeport (Plaza West Bldg.) 250 Units (55 and over) Garden City – 117 Units

Glen Cove (The Villas) – 176 Units

Glen Cove (Garvies Point) – 1,110 Units, 12 stories high Gordon Heights – 118 to 340 Units

Great Neck Estates (Middle Neck Rd.) – 40 Units

Great Neck Plaza (5-9 Grace Ave.) – 30 Units

Great Neck (Plaza Landmark) – 93 Units

Great Neck (Avalon Bay, E. Shore Rd.) – 191 Units

Hampton Bays (Canoe Place Inn) – 37 Luxury Apartments Hauppauge – 150 units

Hauppauge – 98 Senior Apartments (Joshua Path)

Hempstead Village – 3,400 Units

Hempstead, Harbor Island (Cibro Oil property) – 140 Luxury Apartments

Hempstead (Island Park, Barnum Island) – 86 Units

Hempstead (Bedell & Main St.) – 240 Units

Hempstead (Washington & Front Streets) 336 Units

Hempstead (Village Loft) 29 Units

Hempstead (Hempstead Ave) – 12 units

Hicksville (North Broadway) – 350 Units Holbrook (Islip Pines) – 450 Units (NE corner of Vets. & Sunrise) Holtsville – (The Bristal – No. Ocean Ave.) – 140 Units – (Assisted Living)

Huntington (Oheka Castle) – unknown

Huntington Station (West Hills Rd) – Assisted Living – 90 Units

Huntington Station (Country Pointe) – 76 Units

Huntington Station – 379 Units Huntington Station (Ruland Rd) – 117 units

Huntington Station, behind Gateway Plaza (NY Ave. & Olive St) – 66 Units

Huntington Station (Northbridge St. & New York Ave.) – 16 units

Islip (Freeman Ave.) – 96 Units

Islip (Main St., Spin City Realty) – unknown units

Islip Terrace – (Wantagh Ave.) – 26 Units (55 & over) Jericho (Town of Oyster Bay, Underhill Rd.) – 280 Units – Assisted Living

Kings Park (Main St. Revitilization) – unknown

Kings Park (Upland @ St. Johnsland) – 80/199 Units (55 and over) Knoll Farm (Brentwood) – 240 Units (nixed) Lake Grove, The Bristal – 136 Units (Assisted Living)

Lindenhurst – (Gail Grace Manor) – 29 Units (55 and over)

Lindenhurst – (Hoffman Ave.) – 260 Units (defeated by the board & Historical Society 1/2017) MAY BE APPROVED NOW

Lindenhurst – (Bower Elementary School) – 100 Condos (55 & Over) $400,000 per unit

Long Beach (Superblock, Broadway & Broadwalk) – 522 Luxury (15-Story)

Malverne (Hempstead Ave.) – 12 Units Condos

Manhasset (Community Drive) – 72 Units (Affordable Senior Housing)

Mattituck – 75 + Units (affordable housing) Melville (Sweet Hollow Park) – 261 Units (affordable senior units) Melville (Huntington Quadrangle – Rechler) – unknown as of 6/6/15)

Middle Island (Middle Country Rd.) – 123 Units (half Veterans, half affordable) Concern.org Mineola (Mill Creek) – 311 Units

Mineola (former Corpus Christi Elem. School, Searing Ave.) – 192 Units

Mineola (Mineola Properties (metro), 199 Second St.) – 266 Units

Mineola Master Plan (Old Country Rd. & Mineola Blvd.) – 1,460 Units

Mt. Sinai, Pond View (Canal Rd.) – 97 Units (55 and over)

Mt. Sinai, The Ranches – 230 plus Units (55 and over)

Mt. Sinai, 35 Acres (King Kullen Center) – 200 plus Units (55 and over)

New Cassel – 68 Units (Affordable Senior Housing) Nesconset – (Pierson St. & Wilson Avenue) – 66 Units

Nesconset (Story Brook Meadows) Smithtown Blvd. 23.17 acres – 192/228 Units (55 and Over)

North Hills (Ritz-Carlton Residences) – 121 Units

Oakdale Center – 109 Units

Patchogue – (assisted living) – 146 Units Patchogue (New Village) – 291 Units

Plainview (Country Pointe) – 792 Units Port Jefferson (Shipyard on W. Broadway) – 112 Luxury Units

Port Jefferson (Overbay – W. Broadway) – 52 Units Port Jefferson Station Hub, Texaco Ave. & Linden Pl.(THE HILLS) – 74 Units Port Jefferson Station Hub, Tsunis Property – 97 Units

Port Jefferson Station Hub – 800 Units approx.

Port Jefferson Station Vista at PJS (Bicycle Path) – 245 units

Port Jefferson Station (Assisted Living) – Route 112 – 170 rooms Port Jefferson Station (vacant Ramp Motors) – 85 Units (55 and over)

Port Jefferson Station, Heatherwood Golf Course – 200 units (55 and over)

Riverhead – 97 Units (48 units @ Science Center & 45 units @ Peconic Crossing)

Riverside (Southampton Traffic Circle) – 2,200

Riverhead (McDermott & Main St.) – 118 Units

Rockville Centre – 349 Units

Ronkonkoma Hub – 1450 Units

Ronkonkoma (Portion Rd.-30 Units for Veterans) – 50 units (Concern.org)

Sayville, The Bristal – 144 Units (55 and over)

Sayville, Village Green – 64 Units (55 and over)

Sayville (Lincoln Ave. & Sunrise Hwy.) – 64 apartments

Sayville (Island Hills Golf Course, Lakeland Ave.) – 1,600 units

Seaford (Seasons) – 112 Units – Condos

Selden (mini-golf course) 126 Units

Setauket (Pond Path & Route 347) – 130 units (55 and over)

Shirley – 450 Units

Smithtown – Lumberyard – 56 Units

Smithtown (Whisper Landing) – 103 Units (Assisted Living)

Smithtown – Concrete Plant – 260 units (tabled for now)

Smithtown, Whisper Landing – 136 Units (55 and over)

Smithtown, Uplands @ St. Johnland – 175 Units (55 and over)

Smithtown (New York Ave., former site of Administration Bldg.) – 250 units

Smithtown (Country Pointe) – unknown number (55 and over)

Southampton (The Hills, Golf Course) – 118 units, assortment

Southampton (Oak Beach Inn) – 37 Units

Southampton – 73 Units

Speonk (North Phillips Ave.) – 38 Units

Stony Brook – near Baptist Church location – unknown units (student housing?)

Syosset (Cerro site) – 515 Units + 110 Single family homes

Tuckahoe – 28 Units

Uniondale (Nassau Coliseum) – unknown units

Valley Stream (Gibson Blvd.) – 39 Affordable Units

Wheatley Heights (The Colonial Springs Farm) – 264 Units

Westbury – Meadowbrook Point – 720 Units – Luxury Condos

Westbury (The Vanderbilt) – 195 or 178 Units

West Babylon (the Bristol, Route 27A)

West Sayville (Pollack Gardens) – units (Concern.org)

West Sayville (Island Hills Golf Course) – 1,600 Units

Westbury (The Source Mall) – unknown units

Woodbury (Woodbury Rd.) – 95 Units – 55 & over

Wyandanch (Straight Path & Station Dr.) – 167 plus Units

Wyandanch Rising – 1,200 Units

Yaphank (Rocky Point Rd.) – 112 Units (Concern.org)

Yaphank/Shirley (The Boulevard @ Yaphank) – 850 Units – affordable

Yaphank (assisted living) @ The Boulevard – 118 beds

BARCLAYS CENTER, BROOKLYN – 2,200 Units

5 Pointz – Queens – 1,000 (includes 210 affordable) Units

Citi-field surrounding area – unknown

Wow, wow, Natalie.

It readily appears that this article with who and what they represent and whose money and interests they represent are soft soaping the Long Island suburban populace. It’s as if they don’t care and it’s all about the ‘buck’. Their bucks.

The down sides of destroying suburbia are never mentioned. It’s always the ‘horse before the cart’. Where are the Long Islands ‘JOBS’ needed to support all this housing ? Where are the people coming from to fill these vacancies ? What do density housing projects offer to the culture, life and stability of suburban Long Island ?

There is such a thing as over-building. I don’t think they care !

Example of the clear cut system. Smithtown General will be the site of some new stackem and packems. Pre-construction sales to begin soon at the Huntington site and are to be ready for move in 2018. At least these are to be purchased condos and not rentals, they will be starting at $600,000. Nothing like downsizing with a price tag more than the median cost of the homes on Long Island. *The median price of homes currently listed in Suffolk County is $488,900.

The property is 11.5 acres, how much clear cutting will be done on this site? They have clear cut so much of all these properties, it isn’t funny. Not a tree left standing. Our air quality is poor, we need those trees! Never a tree hugger in site on one of the thousands of acres of trees that have been clear cut! Just look at the projects on William Floyd they clear cut 100s of acres! They do this on almost every one of the projects listed by Natalie!

They have clear cut so much of all these properties, it isn’t funny. Not a tree left standing. Our air quality is poor, we need those trees! Thousands of acres of trees that have been clear cut! Just look at the projects on William Floyd they clear cut 100s of acres! They do this on almost every one of the projects listed by Natalie!