The following was written for The Real Deal, and published in the special New Jersey section on June 6, 2016. You can read the original here.

With an increasing number of companies moving toward urban cores, the future of New Jersey’s sprawling suburban office parks and large corporate plazas is in question.

The Garden State, in particular, is vulnerable to sweeping trends in the use and subsequent obsolescence of traditional low-slung and sprawling office parks. Stephen Stirling of NJ Advance Media wrote in a piece last year, “The New Jersey office park isn’t what it used to be, and the state’s job market is suffering for it.” Stirling went on to call New Jersey’s office sector a “job-sucking albatross.” And when Newmark Grubb Knight Frank writes a report titled “Suburban Office Obsolescence,” as they did in September 2015, it’s clear that something is amiss.

“Dated, vacant office and industrial properties do not benefit anyone,” said Mark Fogel, the president and CEO of Jericho-based ACRES Capital, which finances commercial projects in New Jersey.

Ever-evolving office needs have created a “shift to more urban and dense communities as access to amenities and easier transportation options have become key factors for residents and commuters alike,” he said, noting that continued growth in telecommuting has allowed companies to perform productively with less space and related costs.

In New Jersey, these dated and vacant sites are numerous, which can be problematic for their owners and the leasing agents hired to fill them, as well as local officials.

From 1980 to 1990, New Jersey experienced “the greatest office building boom in history” thanks to the creation of over 100 million square feet of office space, James Hughes, dean of the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, told The Real Deal.

When discussing these developments, Hughes mentioned five factors that have pushed suburban sites out of sync with today’s needs. Those factors include the absence of technological amenities, geographic locations far from typical neighborhood services and the urban core, demographic shifts in workforce and corporate needs in New Jersey, rapid advances in information technology that allow for more flexible work situations and the continual retirement of baby boomers.

Hughes noted that while some municipalities are sticking their heads in the sand regarding the issue, others, such as Somerset County, are getting creative with their office sites.

Ralph Zucker, the CEO of the local real estate firm Somerset Development, has experience with the potential successes these blighted parcels can bring. He also is familiar with finding creative ways to repurpose these office sites for more modern usage.

Left to right: James Hughes of Rutgers, Peter Cocoziello of Advance Realty and Ralph Zucker of Somerset Development

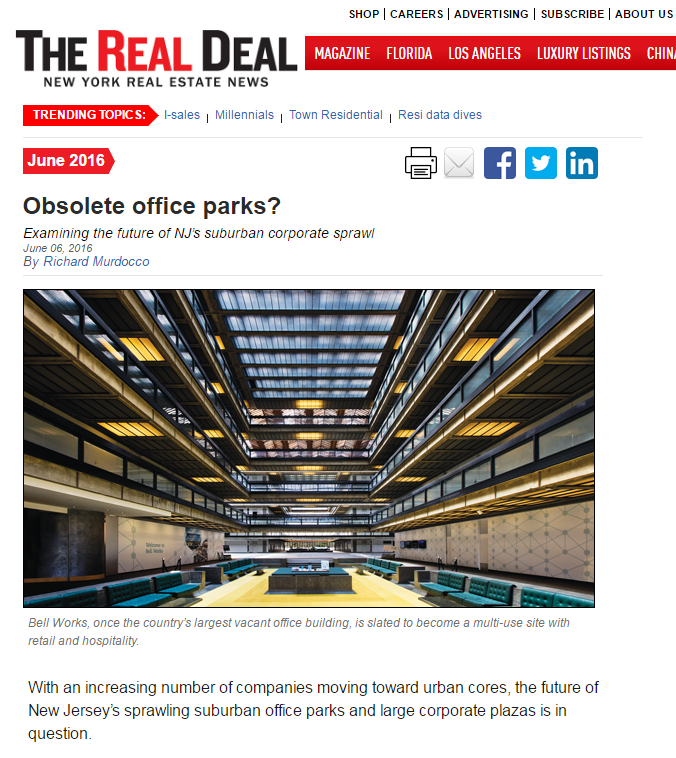

In September 2013, Somerset Development purchased Bell Labs in the Holmdel Township of Monmouth County, once the largest single vacant office building in the U.S., for $27 million with plans to redevelop the roughly 473-acre site to include retail, hospitality and restaurants.

As Zucker put it, most suburban office parks were “mind-numbing places” that were “designed, located for a different era.” With Bell Labs, the large parcel had an “awesome design, and awesome location” that could be easily transformed, he said, because it was already designed to be an adaptive, collaborative space — fixtures of today’s office environment.

Somerset Development transformed Bell Labs into a large mixed-use property, now known as Bell Works, which includes 225 residential units that sell at market rate. This all worked to create a “live, work, play” atmosphere, Zucker noted.

“Not every office park has the right bones, but it can work,” he added, giving caution to those looking to emulate his redevelopment model. Having the proper infrastructure and zoning is key to the success of these sites, according to Zucker. And many suburban office parks suffer from “bad politics, bad zoning, bad location and bad design,” a confluence of factors that is hard to recover from, he emphasized.

With the creation of Bell Works, the challenge wasn’t so much laying down a foundation for growth but instead showing the community its value, Zucker said. It took the developer five years to get the zoning change he needed to move forward with the project. The as-of-right zoning at the time called for a single tenant to utilize the property’s 2 million square feet of single-use office space and the site remained on the market looking for a tenant for longer than Zucker and his team had intended.

Fogel noted that while some companies still find utility in sprawling suburban office campuses — particularly medical office, drug, research and biotechnology firms — repositioning these sites to meet the needs of residents and workers in the 21st century is critically important for the state’s economic future.

For many New Jersey municipalities, revitalizing the most underutilized office parks remains a priority when it comes to keeping their coffers filled, according to the local officials and developers who spoke to TRD.

However, as with all development matters, resident support is critical for any of these efforts to be effective. The real estate community has recognized this by calling for walkable, transit-oriented development to adapt to changing tastes. But the challenges in doing so involve measuring market demand and assessing community needs in addition to upgrading outdated infrastructure.

The NJ Center of Excellence has been redeveloped on a former 110-acre pharmaceutical company site in Bridgewater.

“Everybody wants the big-time rateables that international companies bring, but nobody wants to create the global infrastructure they need,” said Peter Cocoziello, the president and CEO of the Bridgewater-based real estate development, investment and management firm Advance Realty.

Cocoziello said that today’s millennial workforce is connected and urbanized and that employers are following suit. While the developer admitted that “live, work, play” is an overused term in the real estate industry, the notion is helpful to strive for when redeveloping such vacant properties.

In April 2013, Advance Realty took on the task of reshaping the former Sanofi U.S. Research and Development Campus in Bridgewater, a 110-acre site that at the time had 1.2 million square feet of vacant space. The Sanofi site was divided into two sections. The first, constructed in the 1960s, was deemed obsolete and is slated for demolition, while the second, constructed in the 1980s, is currently attracting new tenants.

Thanks to a recent zoning approval that allows for 400 apartments, 75,000 square feet of retail and a hotel, the site is thriving in its post-office park life as a centralized town square, all while still leasing to big multinational tenants such as Nestlé Health Science, which will move to the area early next year.

Executives at Nestlé Health Science told Bridgewater Mayor Daniel Hayes in October 2015 that the company was looking to relocate from Floram Park to an area with the community amenities that Bridgewater offers. After the subsidiary of the food research giant agreed to come on board, he was convinced that the municipality was on the right path to attracting tenants. By “fishing with the right bait, for the right fish,” as Hayes told TRD, Bridgewater and Advance Realty worked to reposition the idle site.

While Cocoziello said his model of growth is bolstered by community support, he cautions against using a broad brush to define New Jersey’s 566 municipalities and 22 counties when it comes to their position on revitalizing such office sites.

“There are always people who believe NIMBY and those who are believers [in the projects],” he said. “You need to be able to get the necessary approvals — some are really good and some just don’t have it.”