The following was written for The Long Island Press on March 17, 2015. You can read the piece here.

Could one small township have the power to approve the largest development project in Long Island’s history? That seems to be what’s shaping up for Jerry Wolkoff’s ambitious Heartland Town Square for the former Pilgrim State property in Islip Town.

Wolkoff is taking an all-or-nothing approach to the project. Heartland could affect the future of Long Island.

As the 1990s dawned, Pilgrim State Psychiatric Center, once one of the largest such mental institutions in the world, was in its twilight. Psycho-pharmaceuticals were growing in popularity for treating severe mental illness, and large-scale psychiatric treatment centers like Pilgrim had become obsolete. Decentralization had already led to Edgewood State Hospital, Pilgrim’s sister center in Deer Park, being shuttered and demolished. The western portion of the Pilgrim property had been subdivided in 1974, eventually becoming home to the western campus of Suffolk County Community College.

Now planners were anticipating what lay in store for the remaining large tract of land that Pilgrim State had occupied for decades.

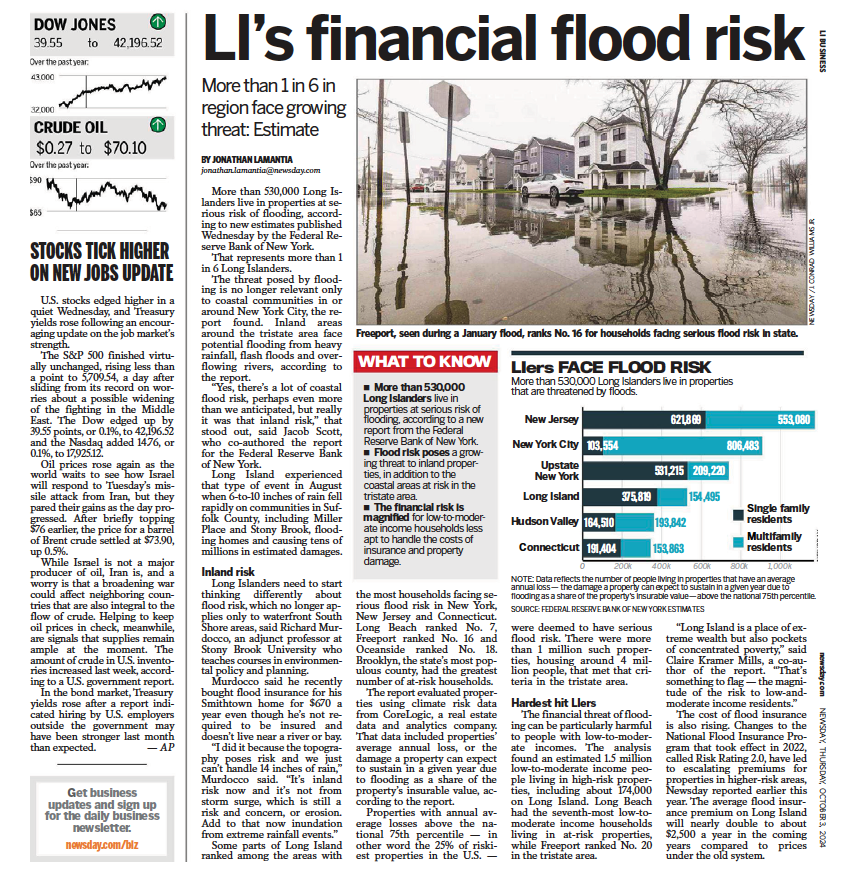

The 1992 plan for Pilgrim State’s property arose out of environmental necessity. The Long Island Comprehensive Special Groundwater Protection Area Plan, a crowning achievement of environmental planning and policymaking by the Long Island Regional Planning Board, staked out the property’s fate with modest recommendations for development. Their findings had determined that the Pilgrim State properties, as well as the former Edgewood site, a total of 3,000 acres, were—and still are—hydro-geologically important for recharging Long Island’s freshwater underground aquifer. Subsequently, the site was named specifically as the Oak Brush Plains Special Groundwater Protection Area, or SGPA for short.

The SGPA plan recommended halting development until the site could be completely hooked up to the sewer infrastructure of the Southwest Sewer District and immediately reducing its potential for illegal dumping and storage. It called for subdividing the property into large lots for “dry” industrial usage that minimized the risk of noxious spills and production waste, as well as commercial development and ensuring “the quality of future non-residential development in the area.” Last but not least, it urged the State, Suffolk County and Islip Town to “maximize the preservation of existing open space within their respective holdings so as to protect the remaining undisturbed recharge areas.”

While the special groundwater plan was being formulated in the early 1990s, the Long Island Pine Barrens Society filed a lawsuit to freeze future development in critical areas of Long Island’s aquifer until a long-term strategy to protect our region’s vulnerable water supply could be created. In an op-ed in The New York Times, David Stern, who was then-executive director of the New York State Assembly’s Legislative Commission on Water Resource Needs of Long Island, warned that “development projects approved before the lawsuit was filed are being constructed in these areas. Many municipalities that have the absolute authority on development within [the] protection areas have blatantly ignored their importance to Long Island’s groundwater by approving overly dense developments.”

More than 25 years later, Stern’s words are still just as true today.

By all accounts, Jerry Wolkoff is a very driven individual. Starting in 1984, he built the Heartland Business Park, which spans roughly 500 acres. Then in 2001, he purchased 460 acres of the 778-acre Pilgrim site for around $20.1 million. As The New York Times put it, “With the purchase of Pilgrim State, Mr. Wolkoff will own more than 900 contiguous acres of land in the Town of Islip, including Heartland, which is adjacent to the Pilgrim site.”

By any measure, Wolkoff’s Heartland Town Square is a monumental proposal. For the 452 acres, Wolkoff wants to change the current as-of-right single-family residence zoning district to a new “planned-unit-development zone”, or PUD for short. The current zoning has each unit on a 40,000-square foot minimum lot size, which is more in line with the less-impact development called for by the SGPA plan, while the new PUD zoning significantly increases the developmental density. The breakdown of proposed usage is as follows:

• Office Space: 4,039,500-square feet

• Retail: 1,030,000-square feet

• Civic Space: 110,500-square feet

• Residential: 9,130 housing units

• Total: 15,500,000-square feet

The project would be built out in three five-year phases, with the total project taking 15 to 20 years to reach completion. So far, the ground has not been broken but some work has commenced, such as demolishing an old LIRR bridge over Commack Road and beginning some preliminary utility projects. Some projections say that 20,000 new residents may eventually live there. But who knows if they ever will.

Not much has changed on Long Island since Wolkoff first announced his ambitious plans…except that the climate has become much friendlier to developers overall. In recent years, multi-family developments have been in vogue, with projects such as the Ronkonkoma Hub and Wyandanch Rising grabbing headlines in the papers and approvals by the municipalities. Suddenly, the humongous Heartland Town Square seems to fit the bill. After years of delay, the Islip Town Board finally signaled that they were more open to the project when they adopted the proposal’s Final Generic Environmental Impact Statement last May.

Over the years, the project has run into more than a few delays, but one particular point of contention between Islip and Wolkoff still remains: Who exactly will pay for the public improvements that will be necessary to allow for such colossal growth? Payment of what are called mitigation or impact fees is often debated whenever a development is being proposed, but the burden of cost in this case is particularly heavy. Substantive roadway upgrades will be needed on the Sagtikos Parkway, Long Island Expressway and other local roads to handle the proposed growth as each phase is completed. Improvements include additional lanes on the parkway, which would impact every interchange along the route, as well as the potential for an additional lane on the LIE, which would be a massive undertaking. These two large projects eclipse all the local roads that will need widening as well as other modifications to allow them to handle the additional traffic volume Heartland is slated to generate.

Simply put, if Wolkoff gets his increased density approved, the public improvements should be financed by the developer. Currently, the level of service on Long Island’s roads, graded like a middle-school essay from F to A, is at a mediocre B, at best. The Heartland proposal would put undue burden on the neighboring communities, and residents should not have to shoulder the costs to maintain the currently deplorable condition of our road network.

Not all of Wolkoff’s entire proposal is bad. His preservation of an elegant pre-existing brick tower that once supplied Pilgrim’s water needs as the focal point of one of the many new residential districts is a nice, tasteful adaptive reuse, as is the proposed repurposing of the former power station into an art gallery.

Development of the Pilgrim site should happen, but not at this scale.

After the first phase is completed, the Town of Islip and its residents should stop to assess the economic climate, study the regional inventory of commercial, office and residential needs, and adapt to the new regional conditions. Why should we oversaturate the region with unnecessary growth that will have impacts far beyond the Town of Islip’s borders? Long Islanders pride themselves on the principal of home-rule, which prides itself on the ability for a local community to control its own land usage, but mega-projects like Heartland justify the need for strong, unfettered, comprehensive regional planning.

It is critical for Long Island’s residents to remember that there is a marked distinction between “builders,” who often seek to profit from development, and “planners,” whose goal is the long-term vibrancy of the community. The goal of planning is to balance development and preservation within the existing community framework.

Long Islanders cannot let Heartland—and Heartland alone—dictate the future of not only the Town of Islip, but the region as a whole.

Without taking a comprehensive approach, Long Island’s future is in the hands of the town board members of one municipality. Can we trust them to think beyond their election cycle and their borders?

Rich Murdocco writes on Long Island’s land use and real estate development issues. He received his Master’s in Public Policy at Stony Brook University, where he studied regional planning under Dr. Lee Koppelman, Long Island’s veteran master planner. Murdocco will be contributing regularly to the Long Island Press. More of his views can be found on www.TheFoggiestIdea.org or follow him on Twitter@TheFoggiestIdea.

What about all the wildlife ! Long Island has a whole has become horrible! Remember 10 years ago or so there was no rush hour traffic! People the town of islip selling us out ! Take a hard look behind the old Grumman building in great river … absolutely horrible

Guinness Book of Records once listed Pilgrim State Hospital as THE largest mental hospital in the world.

Tax Increment Financing should be considered as the way development (not necessarily developer) could pay for public improvements off site as the project grows in size.