One year after Hurricane Sandy rumbled up to our shores, Long Island is still woefully vulnerable. Our coastal systems are ill-prepared for storms, our development patterns show minimal respect to our flood plain and erosion areas, and our electrical infrastructure is still antiquated. What follows is a visit to the days leading up to Sandy, and the day-by-day take on the aftermath of the storm. In the immediate days after the storm, the realities of Sandy’s impact started to sink in. It is important to remember the lessons learned from the storm, implement preventive measures and to move forward, all in preparation for the “Next Big One”.

Storm Coming

The storm formed in the early weeks of October, went past Jamaica and churned gradually up to Hurricane strength. People joked about the early hype, calling it “Frankenstorm” and the “Snor’eastercane”…but in the weeks before Sandy hit, the forecasters saw the potential impact the storm could have on the Northeast. By October 25th, We saw it coming, and we knew it was going to be bad. On October 26th, New York Magazine wrote:

“But Weather People are stressing today that they really aren’t overhyping it when they declare that the likes of the Frankenstorm haven’t been seen in the Northeast in 100 years.”

Unfortunately for the region, the predictions were accurate. Sandy, the so-called “Frankenstorm” rumbled up the coast, collided with another storm front from that was moving the west, sharply hooked west, and hit the tri-state region dead-on.

New Jersey’s coast and parts of Staten Island and Brooklyn were decimated, the Rockaways flooded and burned. Downtown Manhattan was inundated with surge , with videos of the subway stations filling with water going viral. On Long Island, Long Beach and anything south of Montauk Highway across Nassau and Suffolk and flooded in ways reminiscent (and in some areas, far worse) than the then-benchmark “Long Island Express” of 1938. Thousands upon thousands of trees fell, telephone poles snapped and homes were destroyed.

The Aftermath

Early on in Sandy’s fury, Long Island plunged into darkness. When residents awoke on October 30th, over 945,000 Long Islanders were without electricity, the LIRR was offline, highways closed and people started taking in what exactly happened on October 29th.

By Halloween, the LIRR started running very limited service, while the City saw limited transit service above 34th Street. There were still 877,000 without power in Nassau & Suffolk. November 1st saw the first rumblings of the gas shortage that eventually gripped the region. County officials urged people to stay off the roads after dark due to safety concerns. At that point, Con Ed estimated roughly a 10-day power restoration period, while LIPA was still contending with 636,000 outages by 10:30pm that evening. LIRR & Metro-North was expanded both railroad’s limited service, and area hospitals began to have lights again.

Post-Sandy Gas line in Centereach

On November 2nd, temperatures dipped down unexpectedly, placing undue burden on the 626,000 residents still without power. Gas lines became more prevalent as current supplies dried up and demand kept rising exponentially with the fear of shortage. While policymaker claimed supplies would open up in the coming days, the public started to hoard existing supplies.

On November 5th, LIPA reported 336.569 outages, and the Governor’s office was responding to mounting outrage over LIPA’s response, calling it “unacceptable” in the media. LIPA estimated that 90% of Long Islanders would have electricity by Wednesday, November 7th. In Freeport, it was reported that the storm surge was record-breaking, reportedly reaching 10 feet and over. On November 5th, it was reported that power outages on Long Island constituted 74% of New York State’s total of 453,940. In reality the figures were far worse, for LIPA’s figures excluded the City of Long Beach, the Rockaways and Fire Island. Damage to parts of electrical transmission system in Kings Park was called “severe”, delaying restoration in parts of St. James for weeks. Gas shortages started to ease slightly, but 2 hour waits on fuel lines and the sight of packs of both LIPA and out-of-state utility trucks were still the norm across the Island. The City enacted odd-even gas rationing, and days later, Nassau and Suffolk followed suit.

By November 6th, criticism and outrage over LIPA’s lack of prepardness and poor communication started to boil over, and the call for reform grew louder as 279,749 Long Islanders were still in the dark. On the 7th, nature’s assault continued with a nor’easter, named “Athena” by the Weather Channel, ripped up the coast, bringing 60 mph gusts, and a freak snowstorm that further exacerbated the plight of storm-ravaged families.

In the following weeks, the damage was slowly repaired across most of Long Island, and gas pumps started filling up once more. LIPA eventually restored power to even the hardest hit areas, and life eventually moved forward to the holiday season for most Long Islanders. However, stalled insurance payouts and FEMA woes delayed our region’s ability to rebound, and for many families, the struggles still sadly continue.

It was estimated that “Superstorm Sandy” as it started to be called by nonprofit advocates and the media, damaged or destroyed 95,534 buildings in Nassau and Suffolk and left behind 4.4 million cubic yards of debris, according to the federal statistics released in January 2013.

Hurricane Sandy Debris Pile in the Town of Huntington

The Time to Act is Now

On December 4th, 2012, I wrote a postmortem on the lessons learned from both Hurricane Sandy & Tropical Storm Irene that was published in both the NYMuniBlog (a blog for municipal leaders), and the Times Beacon Record Newspaper Group. Sadly, the piece is still relevant one year after Sandy exposed our regional weaknesses:

First, there was Tropical Storm Irene, which made landfall at Coney Island in 2011, and now, Superstorm Sandy, which took a sharp leftward turn and struck the Tristate area dead on. Both incidents represent two wake up calls that policymakers and municipal officials must heed. As Dr. Lee Koppelman, Long Island’s veteran planner, always told us at Stony Brook, “The storm of the century is now happening every other year.”

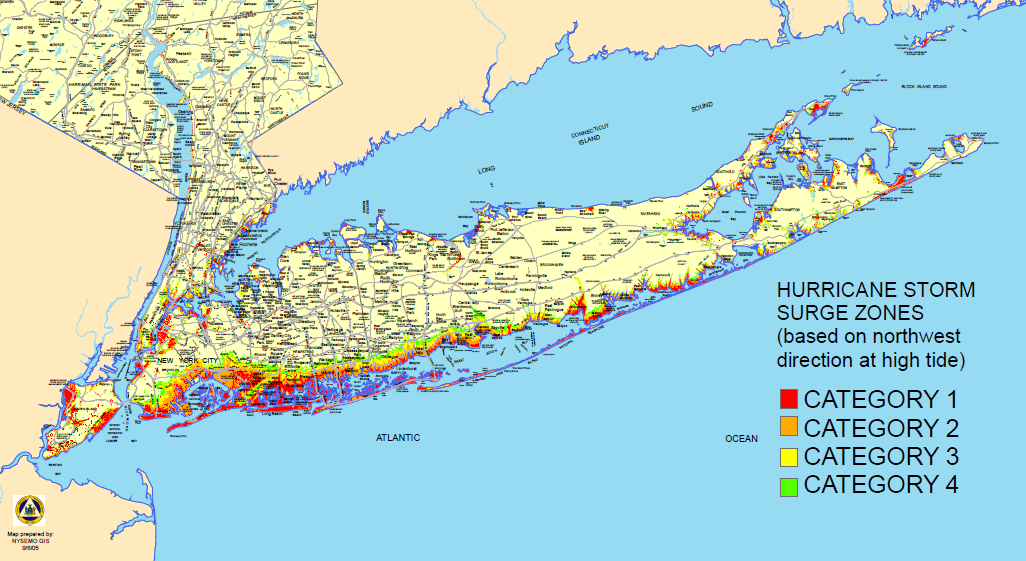

Keep this in mind: As horrible as Sandy’s impacts were, the storm barely was a Category One storm on the Saffir-Simpson Scale. The 1938 “Long Island Express”, which is considered by many to be the benchmark for Long Island’s hurricane threat, was estimated to be a Category Three. That storm created the Shinnecock Inlet, and changed erosion patterns that officials on Fire Island and the Army Corp of Engineers are still dealing with to this day. The damage in the 1938 storm was widespread and spoken about for decades. Since then, Long Island’s population exploded with the expansion of suburbia, and these subdivisions replaced critical wetlands along our shorelines. Post-Sandy, a relatively weaker storm compared to 1938, Long Islanders experienced flooding, fallen trees and destruction that hasn’t been seen in the region.

We must be prepared, and we must adapt our settlement patterns wisely. Planners consider Long Island’s floodplain as the area that stretches south of Sunrise Highway (NYS 27) from the Queens line to the village Rockville Centre, and south of Montauk highway (NYS 27A) to the end of the Island. The south shore is the home to some of the densest population centers on Long Island, and it is imperative that we protect these communities from future storms through smart infrastructure upgrades. The elevation of housing units, natural vegetative buffers and the restoration of wetlands should take priority. On Fire Island, the barrier beach whose geological purpose is to protect the region’s vulnerable south shore from pounding surf, never was an appropriate place to construct residences, and Sandy’s impacts show how dangerous it is to rebuild on the ever shifting sands. We cannot afford to rebuild to the status-quo, we must learn from the lessons of both Irene and Sandy in dictating where future growth will occur.

One Year Later, We Are Still Vulnerable

Paired with the blizzard of 2013, the Nassau-Suffolk region has been hit by large-scale natural disasters that threatened both life and property. Our regional infrastructure is still weak, our systems are still fragile and our coastal areas are still vulnerable. We need to go beyond our current efforts and take substantive measures that are both comprehensive in scope and realistic in implementation.

We need to start restoring natural surge buffers, and moving development away from the coast along the south shore. Our electrical systems need to be updated, and lines must be buried despite the prohibitive costs. Nassau and Suffolk County government and Emergency Services must be on the same page when disaster strikes. Most importantly, there must be open, transparent communication with residents in the days after a future storm. Thanks to technology, there is no excuse for poor public communication. With proper systems in place, we lessen the impacts of the next Sandy.

We were lucky to have a quiet hurricane season thus far, but eventually, our luck will run out. Irene should’ve been the wake up call. Some would even say Hurricane Gloria should’ve opened our eyes to our vulnerability to storms. Sandy now serves as a lesson in what happens when you don’t prepare for the worst, and by many estimates, Sandy was far from the worst-case scenario.

The time to act is now. We, as a region can be prepared, but we must get moving. How many storms will it take before we act?