The following op-ed was published in the July 29, 2019 edition of the New York Daily News. You can read the original version here.

The power broker’s legacy is far more complex than most people now assume

By Richard Murdocco

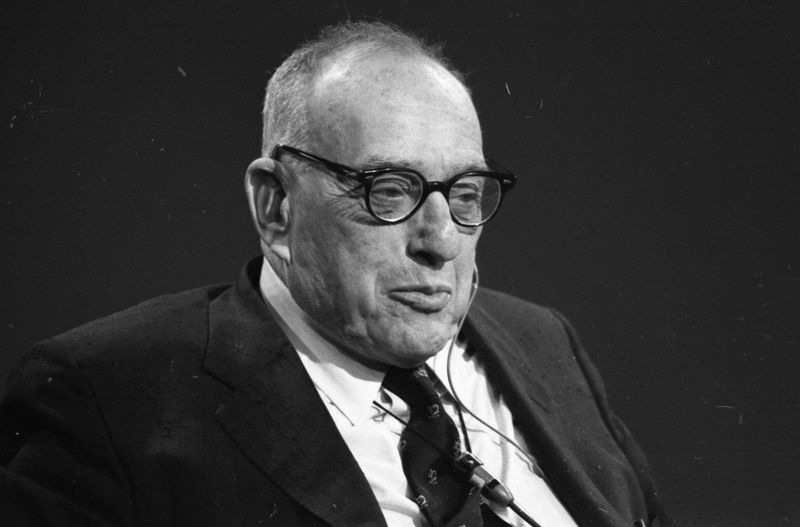

To most, Robert Moses, who died 38 years ago today on West Islip, L.I., was a villain — an unelected dictator who bent New York City to his will with his works of stone, steel and concrete.

Throughout our current era, such a picture of Moses has dominated the popular narrative, painting the builder as a one-sided caricature in a suit who sat atop a bulldozer, looking for the next structure to raze in the name of progress. Many who condemn Moses cite from Robert A. Caro’s “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York” and the exhaustively-researched picture it painted of him.

In painstaking detail, Caro captured the heartbreak associated with the construction of the reviled Cross Bronx Expressway, Moses’ frequent wielding of eminent domain to get what he wanted, and the relentless, unending pursuit of power that eventually consumed a man who once had a starry-eyed optimism about the powers of government being used for the progressive public good.

In reality, the legacy of Robert Moses — and the ensuing tome that Caro spent seven years researching and writing — is far more complex than most suggest.

Dr. Lee Koppelman, a former regional planner for Nassau and Suffolk counties who now serves as head of the Center for Regional Policy Studies at Stony Brook University, worked with Moses in the early days of his career in then-blossoming Suffolk County. Koppelman, who eventually went on to help shape Caro’s telling of Moses, argues that the master builder’s legacy should be approached from two vantage points: his accomplishments with land preservation, and his philosophy regarding transportation.

As developmental pressures rapidly mounted, Koppelman contends that Moses was instrumental in the success of Suffolk County’s earliest open-space preservation efforts. All told, the planner estimates Moses helped the growing local government protect from development nearly 30,000 acres.

“As far as his legacy is concerned, the criticism is always with his approach to transportation,” he told me recently, citing the builder’s aversion to mass transit. That, Koppelman said, more likely stemmed from the political and financial realities of the era above anything else. “But his popularity as parks commissioner for the state, city and Long Island are what established his overall legacy and built the modern framework for the parks system. It is no small achievement that those properties are eternally protected under state law,” he said.

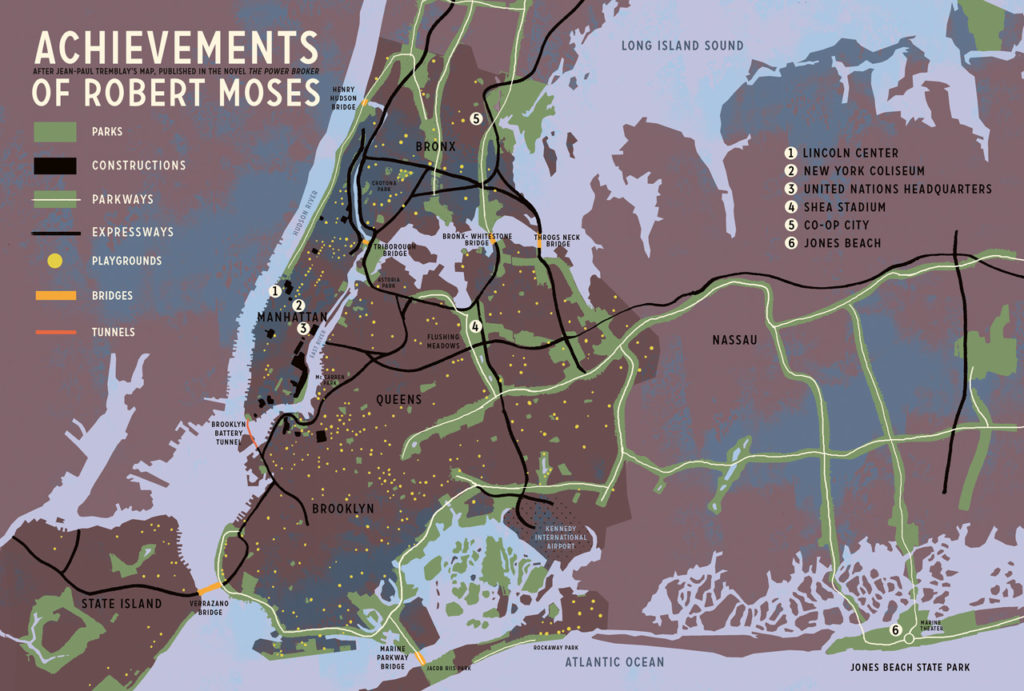

It is important to remember that for every expressway that Moses built, there is a contrasting example like Belmont Lake State Park, which was first established in 1926 in western Suffolk County with 463 wooded acres that were protected in perpetuity from looming developmental sprawl. By 1928, a mere six years since Moses first took control of the then newly-created Long Island State Park Commission, Long Island was home to 14 state parks, totaling 9,700 acres. In New York City, Moses was responsible for the creation of 658 new playgrounds. By the end of his career, Moses was responsible for 2,567,256 acres of protected lands across New York State alongside the bridges, tunnels, housing, civic centers, and more that he built.

Moses was simultaneously both a builder and a protector.

Today, Moses’ name can be found on not only on highways and state parks, but elementary schools and statues in the suburban locale he once called home. The same Moses who unflinchingly wielded power to lay down asphalt also envisioned the splendors of Jones Beach, the crown jewel of our public parks system, and a marvel that today countless arguably take for granted.

Moving forward, it is important to not paint the Robert Moses era with an overly simplistic brush, effectively glossing over the nuances that have shaped where we’ve been. Instead, the complexities of our past must influence where we are headed in the coming years.

To some, Moses will always be the villain they want him to be — a figure that encapsulates the ills of what’s wrong with our physical landscape today.

But to others, perhaps they can think of what might have been if Robert Moses, New York’s master builder, never dreamed of the possibilities on a desolate sandbar in Nassau County all those decades ago.

Murdocco writes on the region’s land use and regional policy issues at TheFoggiestIdea.org, and is an adjunct professor of economic development and planning at Stony Brook University.

nice article Rich

I don’t know how you can write about Robert Moses and not even mention racism. His role in reproducing/producing segregation in New York City and Long Island remains unparalleled. Yes, he was instrumental in preserving open space as parks — but he was absolutely critical in preventing public access to those parks.